| Biographical Non-Fiction posted December 27, 2015 | Chapters: |

...7 8 -9-

|

|

Mona Lisa and the Amazons

A chapter in the book Poetry and Poison

Poetry and Poison: Chapter 9

by Sis Cat

| Background When both parents died eleven weeks apart, their son, Andre Wilson, embarked on a quest to discover what happened before, during, and after their marriage. |

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER

“Do you recall a period in your childhood when Mom didn’t live with you.”

I heard silence on the other end of the phone. Terry broke it. “Come to think of it . . . there was a period when Mom did not live with us?” He referred to himself and our oldest brother Dion.

“How long was it?”

“Oh, a couple of weeks . . . maybe a month.”

Mom was in a mental hospital for a month. Her essay made it sound like she stayed a couple of days. “What happened to you guys? Who took care of you?”

“We went to live with Aunt Edna up in Oakland, and then she came down to live with us in Los Angeles. Grandma Dawson came to live with us, too, and cousin Thaddeus. We were living on 57th Street then.”

I opened the kitchen drawer, grabbed a marker, and wrote notes on the refrigerator dry erase board. “When was this?”

“About 1961.”

1961? That was two years after the events chronicled in our mother’s essay but two years before her marriage to Fred. Are we talking about the same commitment to the psychiatric ward, or did she have a relapse after her essay concluded with “a different Mommy would be coming home to four little waiting arms”?

“Did anyone explain anything to you what was happening to Mom?”

“No one explained anything to me. You may want to talk to Dion. He’s older than me and may provide more information or a different perspective.”

I added “call Dion” to my mental to do list and asked a final question. “Did you notice any difference when Mom came back from the hospital?”

“I really could not tell any difference. She was her regular Mom self.”

In August of ‘63, Dr. Martin Luther King thundered his “I Have a Dream” speech before a crowd of 200,000 in Washington, D.C. Five months earlier, Fred Robert Wilson had a dream, too—to design the Capitol’s first monument to a Negro, educator and civil rights leader, Mary McLeod Bethune.

Around the country, local chapters of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) held fundraisers to erect a monument to its founder in Lincoln Park and not on the National Mall. When the Fine Arts Committee of the Los Angeles chapter of NCNW announced plans for a fashion show and art fundraiser a week before Easter 1963, Fred pounced on the opportunity to win the commission and “breakout” from being a potter. He accepted a slot on the program alongside Rosalind Whelden, a UCLA art instructor who lectured about the role of art in contemporary America; Yong Ho Chi, a Vietnamese painter who demonstrated portrait techniques; and a Negro soloist named Julius Caesar, of all things. Fred planned to stand out from the “rabble.”

In the months leading up to the event, Fred carved and sculpted women—Indian Woman, Woman in Pain, Hold on Little Woman, Calling Mother. Measuring less than three feet high, these sculptures showcased his potential as a monument maker if they were enlarged to life size. They also appealed to the women who would decide the Mary McLeod Bethune Monument.

Since 1962, as the Civil Rights Movement swirled around him, Fred sensed that the roles of men and women would change in the 1960s. Women's emancipation would become the next great social movement to sweep the country and the world. He planned to become its sculptor.

He sculpted “Ductless Man.” It portrayed a nude woman holding what appeared to be a gangly boy clinging to his mother but was a man who had shrunk while the woman grew. If people confused the two as mother and child, he explained, “This sculpture is about the dwindling stature of man. As woman reaches her full potential, man becomes a child in the arms of woman.”

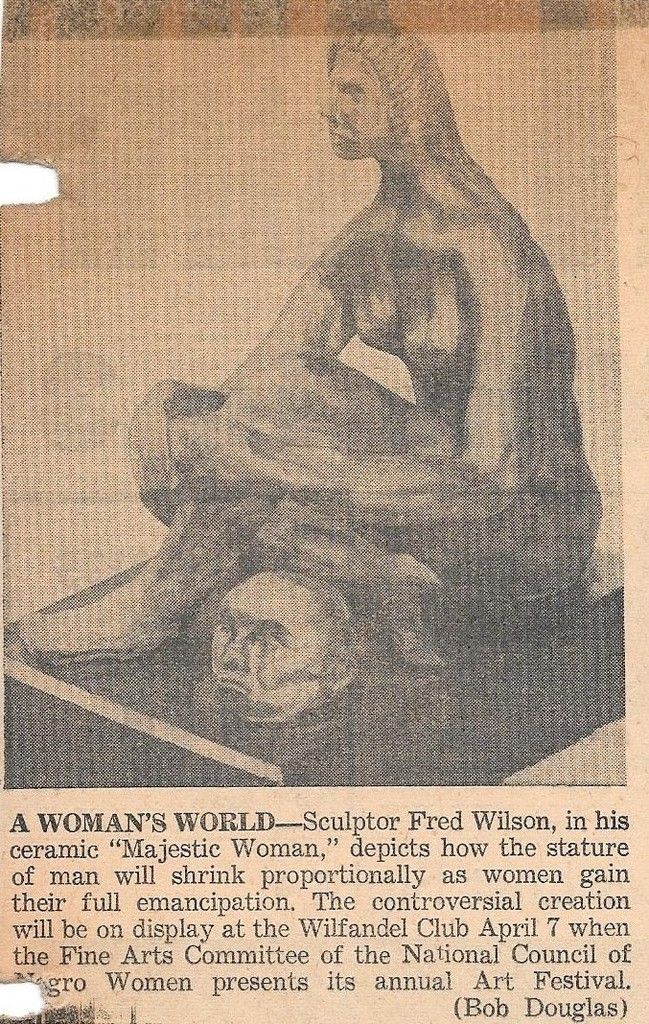

He solved this perception problem with “Majestic Woman.” Instead of a standing nude woman, he portrayed a seated nude woman behind the head of a man. While she grew to majestic stature, his body shrank so that all that remained was his full-sized head, alive and staring in wonderment at the changed roles of men and women. Borrowing an idea from his idol Michelangelo, who had portrayed himself in sculptures and murals, Fred portrayed himself in the head of the bald man.

He would prove that he could compete in the art world as he did in the sports world as an athlete in football, basketball, and track in high school and college. He also played chess. Life was a game of chess. With only two weeks to go before the art festival, Fred picked up the phone and called The California Eagle, a Negro newspaper in Los Angeles.

On the morning of Thursday, March 28, Fred’s clay splattered hands opened the paper. He grinned at a photo of Majestic Woman atop page two. He read the caption:

A WOMAN’S WORLD—Sculptor Fred Wilson, in his ceramic “Majestic Woman,” depicts how the stature of man will shrink proportionately as women gain their full emancipation. The controversial creation will be on display at the Wilfandel Club April 7 when the Fine Arts Committee of the National Council of Negro Women presents its annual Arts Festival.

He rolled the word “controversial” around in his mind. Controversy improved sales, and may win him the Bethune commission. He skimmed over the other artists and the fashion show plans mentioned in the article and read the parts about himself:

Great sculptors on accassion heighten their message by deforming their figures. Wilson utilizes this approach in his sculptural portrayal of the idea that the world will become a woman’s world.

The former athlete, never a great speller, Fred had misspelled in his written statement he gave the paper the word “occasion” as “accassion.” The editor, figuring it was an artsy French word, left it uncorrected. The beginning of the article, “Art Festival to Show Sculpture, Painting,” also titled the sculpture as Magnificent Woman instead of Majestic Woman. Despite the flaws, publicity was publicity. C. Marie Hughes wrote seventy-five percent of the article about him. She concluded by mentioning his art awards at county fairs and his study at California state colleges. With half-moons of clay embedded under his fingernails, Fred cut out the article and prepared for the show.

#

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa, men have named you

You're so like the lady with the mystic smile . . .

Nails scrubbed, Fred, dressed in a black suit and a skinny tie, groaned as the daughter of the NCNW Fine Arts Committee chairman, A. C. Bilbrew, crooned Nat King Cole’s song “Mona Lisa.” Behind the singer dressed like Lena Horn, a woman artist drew back a red curtain to unveil her huge reproduction of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Three months earlier, the Louvre Museum had loaned the world's most famous painting to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, where a million people thronged to glimpse the painting for twenty seconds each. The NCNW hoped to replicate that Mona Lisa magic with a replica on the West Coast. Filling the Spanish-style Wilfandel Club, a crowd of Negro society women, dressed in Easter finery, hats, and gloves, oohed at the reproduction painted by one of their own. Like exotic birds, they fluttered before the canvas.

Noticing that his own sculpture was not getting attention during this spectacle, Fred wriggled his nose at the artist. She’s nothing but a paint-by-numbers hack. And why are these Negro women praising a bad copy of a white artist?

The piano tinkled. The guitar strummed. The chairman’s daughter sang:

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there and they die there

Fred shoved his hands into his trouser pockets. His polished shoe kicked the carpet. Connections. Connections. It’s all about connections. She only got this singing gig because she’s the chairman’s daughter. How about connections helping me get the Bethune commission?

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa.

The solo ended, thank God. The crowd applauded as the daughter curtsied before the Mona Lisa reproduction. This was real art, the NCNW members acclaimed, and we will auction it off to erect a monument to our beloved founder, Mary McLeod Bethune. Fred sighed.

The rest of the art festival progressed. The NCNW auctioned off “Majestic Woman” to raise money for its cause. The paper’s publicity helped. Some of his smaller sculptures, paintings, and textiles sold, too, with a portion of the proceeds going to the organization. He rocked on his heels. Play nice, Freddie. Play nice.

He made it a point to compliment A. C. Bilbrew. She chaired the Fine Arts Committee which would decide the monument. The tall woman wore a corsage that matched her hat. He shook her gloved hands. “Madame Bilbrew, your daughter is a most talented singer.” He placed his hand on his chest. “I am honored that you invited me to participate in your art festival.”

The woman smiled and nodded. Her hat bobbed. “Why, thank you, Fred. It’s all for a good cause.”

Still no word yet on whether or not he would receive the commission.

He distracted himself by watching the spring fashion show. The models formed an Easter parade down a red carpet. Floral arrangements of lilies, orchids, and daffodils lined the runway and were pinned to the bodices of both the models and women in the audience. The air filled with their fragrance. The gowns swished and their beads rattled. The models appeared to float down the runway rather than walk.

The emcee narrated, “Velma Steverson wears this cotton candy confection of melon chiffon. It comes with a jeweled jacket and a matching jeweled bodice in a floral design. This gown is available at Ruby’s French Shop.”

The audience oohed and leaned forward to examine the fabric. Fred grimaced. Women dress for women. They have to go out and spend money to impress other women. Women have been told, “Forget about love. Money is the most important thing.” I’m trying to tell them to save their souls. Love is still the basic thing.

Love.

Fred had just passed his thirty-first birthday a virgin. Perhaps if his Aunt Liza hadn’t burned his hands on the kitchen stove when she caught the boy masturbating, things would be different. Perhaps if his mother Mama Jennie had stayed in Chicago where there were plenty of Negros instead of following a soldier to Victorville, California where there were few, things would be different. White college administrators only admitted him to desegregate their campuses along with a Negro girl if he promised not to date the white ones. Perhaps if the handpicked Negro female students had expressed interest in him, things would be different. Perhaps.

Fred dreamed of marriage. He had carved two statues titled Wedded Bliss, showing an entwined couple. If only his sculptures of women came to life, like Galatea did for Pygmalion, he would find a wife.

Observing the models at the fashion show, Fred saw them as untouchable. They towered in their high heels and hairdos. He felt small, like that tiny, ductless man clinging to the giantess in his sculpture, or, smaller still, the man’s head sitting at the foot of an Amazon. Who could love a man with clay-covered hands and a clay-splattered bald head?

One model caught his eye because she stood out from other Negro models. She appeared white. Was she a Negro, white, or a Negro woman wearing white makeup? He could not decide. He found himself thinking of the line in that song the chairman’s daughter sang:

Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa?

Or just a cold and lonely lovely work of art?

Wrapped in a Botticelli cloud of chiffon, the model drifted down the red carpet and paused at the end. Her smile never changed. The emcee narrated, “Jessie Thompson wears a yellow chiffon gown with a bodice of dropped pearl loops and crystals. This gown is available at Ruby’s French Shop.”

As the model turned to walk up the runway, the hem of her gown swirled to rise and fall. She disappeared into the model area. Fred raised his eyebrows. She will always be a mystery to me.

The fashion show ended. Fred worked the crowd to make sales and connections. Hope this charm offensive works to get me the commission. A group of women in black cocktail dresses accented with orchid corsages confronted him. A woman who wore a turban of ribbons and flowers looked to her friends for approval before making her comment to him. “Fred, I noticed a pattern in your sculpture. You have these oversized women with undersized men.”

Fred regurgitated his well-oiled artist statement. “I believe this world would eventually become a woman’s world. The stature of man will shrink proportionately as women gain their full emancipation. Once man recognizes women’s great potential and their proper place in society, man will rise once again to the stature he at one time maintained.”

The women smiled and nodded at him and each other.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed that the “white” model gazed at his Woman in Pain. She wore a black cocktail dress with pearls now, but her hair still rose in curls. He turned to the women around him, said with a slight bow, “Excuse me, ladies,” and left them. He whisked across the exhibit room, dodging guests and pedestaled sculptures, but he slowed as he approached the woman. No amount of makeup could hide the hint of sadness he saw in her face which echoed the worried look on his sculpture. She snapped out of her daydream and noticed him. “Oh, you’re the artist?”

He heard the just-off-the-plantation Southern accent in her voice. He lost his Chicago accent in California, but not his speed. “Yes, Fred Wilson.”

“Jessie Thompson. Pleasure to meet you.” She extended a white gloved hand.

He hesitated grasping it, fearing he may still have clay remnants somewhere on his hand. He allowed her to grip his hand, firm yet delicate.

She glanced at his bald head. He noticed her eyes looked up for a split moment. Embarrassed that he saw her looking at his scalp, she stared at the carving. “How much is this?”

Fred rubbed his hands. “That will be twenty-five dollars.”

She reached for her beaded purse. “I’ll pay five dollars down and five dollars a month until the price is paid.”

Fred marveled that the model could talk and make unprogrammed moves. All the robots do is walk down red carpets and smile. Now, one stood a living, breathing woman in front of him, a Galatea come to life. Only a sculpture separated him from Jessie. He knitted his brow and pointed. “Why do you like it?”

“It speaks to me.”

Everyone had praised his sculptures of oversized women with undersized men, but Jessie was the first to notice this small carving of a lone woman in pain. Perhaps if he gave her the statue, he could lessen her pain. He pushed the sculpture towards her. “If you really get the message, you can have it.”

Panic and confusion crossed her face. He could tell she thought he wanted to give her the sculpture in exchange for a date. Men hit on models all the time.

“Why are you giving this to me?”

He averted her glare. His shoulders shrugged to buy time. Think fast, Freddie. Think fast. He pressed his index finger on her forehead and dragged a line of smeared makeup along the bridge of her nose and across her red lips. He examined the makeup on his raised finger and whispered, “Behind all your powder and paint, I discern a spiritual soul.”

She stood there, dumbfounded, with a line down her face, as if she had a split personality.

Better beat a fast retreat, Freddie, before she throws Woman in Pain at you. That would be some real pain—getting hit up side your bald head by your own sculpture.

He turned and sprinted to the door. He greeted the guests entering the exhibit and buried himself in the crowd of women—his Amazon bodyguards—to dissuade Jessie from following. He tensed, waiting for a tap on his shoulder and a slap across his face.

Don’t look back, Freddie. Don’t look back.

TO BE CONTINUED

Recognized |

Yes, the Los Angeles chapter of the National Council of Negro Women unveiled a reproduction of the Mona Lisa while the chairwoman's daughter sang the Nat King Cole song.

© Copyright 2024. Sis Cat All rights reserved. Registered copyright with FanStory.

Sis Cat has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work.