![]()

By tfawcus

There were fond farewells and hurried hugs before we struggled up the steps - late, as usual - wrestling our well-worn cases from the bowels of Haywards Heath station. Hurling ourselves onto Platform 2, we were just in time to witness the departure of the 7.52 to Gatwick. Curses! And, again, curses! We spent the next few moments catching our breath. Then came the slow, guilty minutes of smugly comparing ourselves with the sullied ranks of Monday commuters, deadpan and office bound. It wasn't long before I was squeezing aboard the 8.12 just ahead of Wendy, uncomfortably aware that sensible sardines don't carry suitcases.

The Sussex mists, burnished and burnt slowly away by the sun, were already becoming faded memories by the time we boarded the British Airways mumbo-jumbo jet to Miami. Once again the miracle had been achieved, of fitting four hundred malodorous holidaymakers into a metal tube made for midgets. I got to sit next to a teenage lout who had evidently consumed baked beans for breakfast, a silent but deadly companion. We spent the next half hour on a taxiway, awaiting take-off clearance, Air Traffic Control having been caught unawares by the scheduled 10.50 flight - or perhaps it was just that the fog had been slow to clear.

I had always been led to believe that Miami was a sparkling, glitzy place full of bright lights, and I was not disappointed. If there had been a Richter scale for electrical storms, then this one would have been around magnitude 7, a sound-and-light show to beat all. Our onward flight to Cancun was cancelled. They said the aircraft was unserviceable but I reckon it was just frightened. The ground crew certainly were. No-one was going out in that storm to refuel any damned aeroplane, and so we had the pleasure of two hours in the departure lounge, watching a major international airport collapse gradually into chaos. Airline staff did their best to keep the steadily mounting horde of stranded passengers amused, by directing all those waiting at Gate E21 to go and wait at Gate D2, and all those waiting at Gate D2 to go and wait at Gate F19, thus causing a constant flurry of people on the move and the illusion that some of them were going somewhere. Our replacement aircraft at Gate D2 was so frightened that it didn't show its nose cone until half an hour after the storm was over. We climbed aboard, pulled pillows out, and went to sleep.

An hour later we were awoken with a start. There were airport lights shining through the little square window. The captain was making some announcement about disembarking. Are we there already? Wow! That was quick! Well, no, actually. Our new aircraft has a technical fault and we are still sitting on the ground at Miami. Never mind though, we are all going to get out now, to go and find another one. There is apparently a flight due in from Kansas City in 15 minutes that will take us to our destination. And - surprise, surprise - it does.

That is how, after a super day's excitement, we got to arrive at Cancun, Mexico's answer to the Gold Coast, and how we got to meet up with our American friends in the foyer of the Hotel Caribe International. It was now 3 o'clock in the morning and they had just finished drinking the case of beer they'd brought to celebrate our arrival. Their flight from San Diego had apparently landed early in Mexico City, enabling them to make a better connection than planned and they had arrived 4 hours ahead of schedule. This just goes to show that where there's a yin, there's a yang. Let's just hope it's a snug fit, for we're all going to be together for a while.

| Author Notes | Tune in tomorrow for Part 2 of this knicker-gripping narrative - a trip to Tulum. |

![]()

By tfawcus

The third floor view from the hotel room in downtown Cancun is of the stained walls and peeling paintwork of third grade buildings across the road. Aerials randomly spike the skyline, connecting the population to third-rate television channels. A third of all cars disport chipped paint on rustwork. A third of all advertisements is for American sodas and snack foods. This is indeed a Third World landscape. Bougainvilleas, bright orange jacarandas and wind-stooped palms struggle to persuade the onlooker that there is some elemental force stronger than this crumbling breezeblock landscape, trying to reclaim it and define it once again as an exotic sub-tropical paradise.

Two miles further east, the other side of the roundabout, there are signs to 'La Zona Hotelera'. Soon one comes to a narrow spit of coral sand, some seven or eight miles long, a few hundred metres wide, in the shape of a lucky figure seven. It thrusts east south-east into the sea and then cuts back sharply, south south-west to regain landfall not far from the busy international airport. It encloses the Laguna de Nichupte and looks out over the Caribbean Sea. This is to Yucatan what Nice is to the south of France, what the Gold Coast is to Queensland and what the Costa Brava is to Spain. It is the tourism planner's ideal vision of Shangri-La, an earthly utopia; a parade of palaces, cheek-by-jowl, two thousand rooms apiece, a hotelier's heaven, the full litany, Hyatt, Hilton, Holiday Inn, Marriott and Miramar, Sheraton and Solymar. Goliaths of the industry, separated only by air-conditioned shopping malls, restaurants and bars. Planeloads of tourists are flown in, stripped of their assets, and sent home again, suntanned, with sand in their suitcases, often all in just the space of a single weekend.

By midday on Friday we had hired a car, a Dodge Ram, a dirty great beast of a thing. Soon we were cruisin' through 'la Zona Hoteleria' and headin' down south along the coast road whistlin' Dixie, a hundred and thirty miles to the sacred Mayan ruins of Tulum, perched on the cliffs, bathed in the rays of the setting sun.

Tulum, the 'city of discovery' or the 'city of the dawn', must, in its time, have been a haven for the Toltec priests -- a sort of medieval precursor to Club Med. I rather liked the temple of the descending god, with its squat bas-relief of inverted, rectilinear legs thrust skyward and clad -- as far as I could tell -- in a stout pair of galoshes. Who knows? Perhaps he was cast down from the company of the heavenly host right in the middle of the hurricane season.

The Lonely Planet guide describes the setting thus: "The gray-black buildings of the past sit on a palm-fringed beach, lapped by the turquoise waters of the Caribbean". Somehow that does not quite do it justice. There is no mention of the upside-down god, or the huge iguanas sunning themselves on the ramparts, or evening shadows stretching out across the greensward. At sunset, there is an absolute stillness that captures the majesty of this once proud place, now largely reclaimed by nature.

It is our first real taste of the ancient civilisations of Central America.

| Author Notes | Tune in tomorrow for Part 3: 'The Ticketing Trauma', a tantalising taste of Mexican bureaucracy. |

![]()

By tfawcus

Saturday morning at 6am we catch Air Caribe's morning flight to Belize City. With sublime faith in human nature we have repacked all of our proper clothes in the largest suitcase and entrusted it to the care of the Hotel Caribe International until our scheduled departure to Australia, nineteen days ahead. On this stage of the journey we will be travelling light. Just as well really, for Air Caribe's twin-engine 16-seater Jetstream 32 doesn't look as though it's built to take excess baggage. We arrive at the airport confidently waving our tickets but Air Caribe are sorry, they can't let us board unless we have a pre-paid outbound ticket from Belize as well.

"But..."

"Sorry, señora, it's the rules. Belize immigration won't let you in unless you can prove you will be going out again."

"But... what if we were planning to leave by road?"

"Sorry, señora, it's the rules."

"But... what about these international tickets saying we are going back to Australia on 15th July?"

"Sorry, señora."

"You can buy an outbound ticket to Guatemala."

"But... all the other airline offices are closed."

"Si, señora, that is true."

"So... can you sell us tickets from Belize to Guatemala?"

"Sorry, señora, from Belize we only fly back to Cancún."

"But... we don't want to come back to Cancún ... not just yet, anyway."

"Sorry, señora, that's how it is. I can do nothing. My hands are tied."

After an hour of cheerful banter along these lines, Wendy finally gets the airline to agree to issue us return tickets to Cancún on the understanding that their office in Belize City will refund them again when we get there. This is not the last occasion when we are to find our salvation in Wendy's command of Spanish, not to mention her ability to thump the table and wave her arms in the air until all opposition is quelled.

Our flight follows the southern coast road for two hundred miles to the border town of Chetumal, where we touch down briefly before the final twenty minutes on to Belize City. I check with the immigration officials at the airport.

"No, sir, it is not necessary to show your outbound tickets. After all, you could be leaving us by road, couldn't you... and anyway, you have international tickets showing your ultimate departure to Australia... those are quite sufficient. Enjoy your stay!"

We clear customs and head for Air Caribe's check-in counter. A large gentleman overlaps a high wooden stool under a slow moving ceiling fan. He shrugs his shoulders. Try our office downtown, he suggests. Clearly he is not to be moved. We climb into a taxi and do as he recommends.

It is, I think, twenty five years since my last visit to Belize. A new and much improved airport terminal building has been constructed. In all other respects it might have been yesterday. Our drive from the airport takes about twenty five minutes. For most of the way the road follows the course of the Belize River, a muddy brown monster swirling lazily past the mangroves which line its banks. When the rains come the road floods, but otherwise it is good, one of the few metalled surfaces to be found. Our taxi driver wears a Bob Marley hat, plays Bob Marley tapes on his dusty cassette and gives us, gratis, a Bob Marley view of the political and economic state of the nation.

"Yeah, man - cool. You don't have to tip me but it helps and, hey, I'm a nice guy - so think about it."

He drops us off at the river terminal by the swing bridge in the town centre, which is where we will catch the boat across to Ambergris Caye, about 35 miles away, out on the reef. But not quite yet; first there is a small matter to settle with Air Caribe. Tom and I walk across the bridge and turn left down the main street. The first impression is that we have walked straight onto a film set at Universal Studios. There is a bustle of pedestrian activity on the busy street - roadside stalls selling fresh spices - nutmeg, allspice, pepper - woodcarvings everywhere - baskets of coarse, green-skinned oranges, limes, bananas - handcarts selling soft drinks and an exotic range of coloured ice confections - Caribbean music blaring from speakers in some nearby street café - and everywhere down side streets the façades of old wooden buildings once painted with bright colours now sun-faded to pastel hues. Many are on stilts. They are ramshackle, but solidly built from mahogany and other local hardwoods. There are lopsided verandahs, shuttered windows and urchins playing in compacted mud behind broken wooden fences. Between these are the newer constructions of grey breezeblock, ubiquitous building material of Central America, often left as it is, sometimes splashed with whitewash. And then, here and there, old colonial buildings rise up; imposing Victorian architecture for churches, banks and government buildings, but with an uncared-for look since the foreign officials have long since returned whence they came. Tropical storms and hurricanes raze the town with such regularity each September that in 1970 the capital was moved to Belmopan, 40 miles inland. Belize City remains as it was before, the centre of population and the commercial hub - not huge, but its population of 80,000 is still twenty times the size of the new capital.

Air Caribe has an air-conditioned office half way down the street. The staff are charming, friendly, but sorry - they do not have the authority to refund tickets - they are just an agency for the airline. Refunds can only be made by the head office in Cancún . They would like to help, but... The best they are able to do is to exchange the tickets for ones from Flores, in Guatemala, back to Cancún . We agree to this, since it is our plan, eventually, to fly from Flores back to Cancún on 7th July for our final fortnight on Isla Mujeres, the Island of Mothers. We also book our flight out from Belize City to Guatemala City with TACA, another small Central American airline. The tickets are issued. All is sorted out... or so we imagine!

Back to the boat terminal.

| Author Notes |

In tomorrow's installment we are all at sea - literally. A journey to remember!

|

![]()

By tfawcus

Ambergris Caye is a thin coral island about 25 miles long which lies at the northern end of Belize's 165 miles of barrier reef, close to the Mexican border. The travel brochure made mention of a regular ferry service between Belize City and the outer cayes. Just what did we imagine, I wonder?

An open boat with twin 200-horsepower Yamaha engines? Forty passengers squeezed shoulder to shoulder around its periphery on vinyl seat cushions? Suitcases slung in a careless heap in the middle? A two hour journey? Tropical seas swarming with sharks and barracuda?

If this boat has a Plimsoll line, it is a long way below water level! Small waves slop dangerously close to the gunwale each time another boat passes. Our Caribe captain grins through gold-filled teeth, his long black dreadlocks and tattered beard hanging down over a huge beer gut overlapping khaki shorts, and he has a bottle of Guinness Extra Stout firmly clasped in his right hand.

"Hey dere, man, come aboard! Dis is de Caribbean Lady! Ain't she jus' a real beauty, huh!"

We nose slowly out through the gridlock of boats jamming the river mouth until we reach the open sea then ...wham, bam! Hit those throttles, man! The Caribbean Lady sits up on her cute little arse and cuts a bow wave to make your hair curl. Lurch and slump through the choppy water, she slices her way at between twenty and thirty knots towards the fringe of trees on the horizon, throwing up huge spumes of spray which, caught by the cross-wind, whip back into the stern of the boat saturating the row of clenched-teethed, white-knuckled passengers.

"Better than air-conditioning, eh, man?" El Capitano grins.

Five miles out from the nearest island we slow down and, as if from nowhere, another boat draws up alongside. Luggage is passed hand to hand to a young lad at the bow of the boat, then tossed across the gap to be caught by his counterpart. Wait a moment! Some of that is our luggage! It is quickly followed by the dripping, sodden figures of Wendy, Matt and me! At least half of us are going to stay with each half of the luggage! That is for sure.

The load now more evenly distributed between the two boats, we set off again. This time, sitting somewhat higher in the water, we avoid the bow wave and within half an hour are pretty well dried out. Tom, Jeanette and Jeremy have already vanished around the other side of the island, and are not to be seen again until our eventual arrival. Our boat drops in at a couple of islands along the way, lets off a few passengers and picks up a few more. At Caye Caulker we draw up alongside the town jetty and change boats for the second half of the journey. It seems that we have ended up with all of Tom and Jeanette's luggage and they have all of ours. We hope that we might meet up with them again sometime before the end of the holiday but, although now dry and in more philosophical humour, we are not yet brave enough to predict anything with a degree of certainty.

The second part of the voyage is a little more sedate and I have time on my hands to cast an eye over our fellow passengers. Alongside me there is a young Belizean girl clinging to a two-month old babe swathed head-to-foot in a white towel, save for tiny fingers clutched to her breast and dangling feet encased in two-inch sandals. Beside her, stretched across the lap of another young mother, a 3-year old piccaninny girl lies fast asleep, completely oblivious to the cobblestone thump of the journey. Wendy's neighbour has an old sugar sack across his knee. There is something wriggling about inside. Somewhat nervously she asks what it is. He grins and points to a small rubbery snout poking out of a hole near the end.

"He's my pet raccoon. I don't think he enjoys the journey!"

There are also various tanned youths in t-shirts, a German couple, holidaymakers like ourselves, two old men, faces weathered by sun and sea and, opposite me, an amazing apparition clutching a black cotton bag containing a violet plastic thermos with a pink lid. She's a baby-faced girl, eighteen, perhaps, hair twisted into thin braids, tightly drawn to expose neat furrows of scalp, all wound up in a loose bundle at the back. Coffee blancmange breasts partially encased in a white lycra top rest on a huge roly-poly belly - the whole confection wobbling and shuddering in a most alarming manner with each lurch and slop of the boat. Her arm is adorned with golden bracelets and a strange tattoo like a question mark wrapped in barbed wire, and her fingers are laden with gold rings and finished off with extravagant curved talons painted with gold polish. I cannot help thinking of Circe, in the story of Ulysses. Clearly there is truth in these fables of sirens lurking along tropic shores. This I have seen with my own eyes.

Eventually we arrive at San Pedro, and there are the others on the jetty ahead of us, with smiles on their faces and our luggage at their feet. The Sun Breeze Beach Hotel lies 200 yards south along the seafront. Our luggage is tossed onto a handcart and we stroll along the seafront. Soon we are baled up in a dockside restaurant, easing into cold local beer, broiled lobster and shrimp.

![]()

By tfawcus

Sunday dawned gently. A warm on-shore breeze caressed palms framing the new day's fireball as it climbed from its mantle of cloud on the horizon. Behind, hanging above the treeline like a lantern, the silver disc of a full moon faded gracefully, making final obeisance to the sun god as she slid from view. Today was to be San Pedro's Day, the Saint's Day for this island town with its white-painted wooden church, one door opening straight onto the street, the other straight onto the beach. This town with its cemetery in the sand, its tombstones lifted and cracked and left at crazy angles by some ancient hurricane; sailors' graves still tossed by storm. This town of Caribbean laughter.

After breakfast we hired bicycles and cycled to the southern end of the island, to see what was there. We cycled round Banyan Bay, past a huge white tent full of spiritual singers, clapping hands and waving arms in time to revival tunes strummed out on a steel guitar. The tent was emblazoned in square black letters: JESUS BROKEN AND SHED FOR YOU and it was shaded by the broad green leaves of the banyan tree. It took us about an hour of dedicated pedalling along potholed paths, past mangrove swamps and palm-thatched wooden houses, to complete our journey of discovery. Eventually the road ended triumphantly in a pile of litter, a hundred carrion crows, huge swarms of flies and wisps of noxious smoke - more or less what you'd expect at the town dump, I suppose.

In the afternoon Tom took the boys out on a diving expedition to the reef, Jeanette took herself off to bed, feeling poorly, and we lazed by the hotel swimming pool. The pool was a raised structure surrounded by timber decking, fringed by palm trees and overlooking the foreshore and a short wooden pier outside Gaz Cooper's Dive Belize shop. The wall of the shop was painted with a map of the caye and the reef and proclaimed loudly in capital letters: 'Ten miles on one tank of air! K-10 Hydrospeeder. Fly the Barrier Reef at up to 8 knots! Only at Gaz Cooper's Dive Belize at Sunbreeze Hotel Tel:3202'. You could tell by the four digit phone number that Belize wasn't among the more populated places in the world. I don't think that Tom and the boys tried the Hydrospeeder - I guess we'd all done enough 'flying the barrier reef' on the trip over. Now seemed like a good time to slow down. That, at any rate, was the message I was getting from my second glass of cubré libre, and bowl of soggy poolside chips. The hotel itself had a bit of a siesta air about it, too. Hacienda-style, built around a hollow square with balconies overlooking a central courtyard; whitewashed balustrades half hidden amongst bougainvillea and exotic sub-tropical creepers, yellow ochre paintwork and a red tiled roof, a hammock slung between two palm trees overlooking the swimming pool and beach and, overhead, the angular outline of frigate birds hovering and sideslipping in the afternoon breeze. As Tom would sometimes say: 'I wonder what the poor people are doing today?'

On Monday Jeanette is still sick, and Matthew not much better, so when the boat arrives at Gaz Cooper's to pick us up for a day's snorkelling and picnic, there are just the four of us. Two Belizean boys handle the boat and there are three others on board. One is a young lad who has just finished his social work degree at Washington State University. He is out here living with the family of one of our boat crew. He is doing voluntary work for the Church of the Seventh Day Adventists, helping them to build a school on the island. The others are a couple on what they describe as a trial honeymoon; a Columbian girl and her American boyfriend - both teachers. We set out down the coast to another pier further south where we pick up a surprise. Two surprises to be more precise. They come as a pigeon pair, in full length black wet suits, flippers half a yard long and an array of armament, including harpoons and spear guns big enough to subdue Moby Dick and they are very, but very, macho. Wendy says to one of them that she hopes she won't be swimming in front of him when they start shooting. He is quick to reassure her with his big grin and hairy chest that they are lifeguards with the San Diego Fire Department and that she couldn't be in safer hands, ma'am. We make one more stop to fill a large orange plastic ball full of air.

"I'm going to attach this to fifty feet of rope, explains one, and the other end to my harpoon - so when I spear a monster of the deep he'll swim round and round in a frenzy dragging this, instead of coming after me."

On the way out to the reef they make quite sure that we all understand that they are experts and that what they don't know about diving just ain't worth knowing. Oh, yeah!

| Author Notes | Part 6 - out on the reef, where two firemen show their metal and two Belizean boys show their mettle. |

![]()

By tfawcus

The first place we stop, just on the inside edge, is mainly dead coral, with a few small sprays of purple fan coral and quite a good variety of small, colourful reef fish. We stay snorkelling for about half an hour while our two human barracuda cruise up and down on the outer shelf looking for big game. They come back empty handed but with a good story about the one that got away. It seems they had come across a grouper, weighing about 100 lbs and had a shot at it, but the speargun had been too powerful and the spear had whistled through it and straight out the other side. Our two Belizean boys nod wisely and sympathise.

At our second stop the Belizean boys slip into the water in just their shorts and face masks. One has a short handheld spear - more like a sharpened stick really. They take a deep breath and dive. Several minutes later there’s a splutter of water as one of their heads breaks the surface just behind the boat. He has two lobster in one hand and one in the other. His partner appears on the other side of the boat with a grin. Swimming a lazy sidestroke he pulls a small grouper off his spear and tosses another couple of lobster into the boat. Meanwhile Bill and Ben cruise the outer edge of the reef with the heavy artillery. Within half an hour our Belizean boys have landed almost a dozen lobster, a couple of small snapper and a 4-5 lb trigger fish to join the grouper. Still no sign of Bill and Ben. After a while they return. Bill throws one small, undersized lobster onto the deck with a snort while Ben rummages in his bag muttering, as he looks for a new tip for his $400 harpoon to replace the one he snapped off in a coral outcrop.

We raise the anchor and cruise north up the coast for one last stop before lunch. There is a break in the reef wall here and a deep channel coming in from the open sea. We are told that if we are lucky we may catch a sight of some manatee; they sometimes come here to feed. The manatee is a curious mammal, a sea cow, relative to the dugong of Australian waters and, though no thing of great beauty, its almost human face and spatulate tail are thought to have accounted for tales amongst the early mariners of mermaids and other sirens of the deep. It is possible, I suppose. Perhaps after many months at sea and a particularly generous rum ration... Who knows? Two of our party claim to have seen a small one swimming not far from the boat. One was Jeremy, who had an underwater camera with him at the time so, sometime in the weeks ahead, we may get to see it.

A few hundred yards farther up the coast we stop again; this time so that the crew can clean and gut the fish for our lunch. Within a fairly short time we attract a four-foot barracuda and small reef shark that circle the boat, darting in to tear the odd tasty morsels from offal thrown overboard. Jeremy, who is young and fearless, jumps in with his camera to take photographs. Most of the rest of us are content with the more fractured but relatively safer view from on board. After a while we are joined by a frigate bird hovering overhead. He swoops in to snatch tidbits in mid-air then circles gracefully to take up his position again, above and slightly to the rear of the boat.

From here we head inshore, carefully avoiding a line of poles, the permanent tidal fishtrap of a small village community, and draw in near a lime green wooden hut on stilts. One of the lads wades ashore, soon to return with a basket full of coconut husks. These turn out to be the fuel for our barbecue on a deserted beach at the top end of the island, a feast of fresh lobster and all the other fish which they had caught out in the lagoon. When we have had our fill the boys gather up all that is left over and take it back to the family who provided our coconut husks, for their supper. Waste not, want not.

We set off for San Pedro at about 3pm, stopping one more time to snorkel in a reef garden full of live corals and all manner of brightly coloured fish. This proves to be the occasion when Bill and Ben at last meet with success. They bring in a huge grouper from just beyond the reef, three or four feet long and about 40 lbs in weight. It is a matter of some conjecture among us after we have dropped them off as to whether they will stuff it as a trophy or solemnly slice pieces off it for the next two weeks for breakfast, lunch and candlelit dinners on the balcony of their guest house. I cannot quite throw out of my mind the image of them doing this with full silver service and the finest crystal, gazing fondly across the table at one another, each still neatly dressed in his long black wetsuit, a flaming red hibiscus buttonhole and flippers.

That evening, pleasantly weary from the day’s exertions, not to mention being slightly sunburnt, nothing would have been more welcome to us than to crawl into bed after a hot shower and a couple of drinks at the bar. However, because Matthew is a diabetic, he needed to get a meal, and since he and Jeanette had passed the day quietly recovering from some mysterious sickness instead of spending it with us in paradise, we hauled ourselves off to a restaurant downtown for dinner. The service was painfully slow and we toyed with bowls of soup and glasses of water while the others ate. Meanwhile the sky over the lagoon darkened and distant flickers of lightning set off threatening rumbles which became increasingly ominous. Just as we were about to pay the bill there was a blinding flash and a crack of thunder which shook the foundations. The island was plunged into darkness, people groped their way round the restaurant with candles and torches and the first heavy drops of rain started to beat down on the roof. We half-walked, half-ran back to the hotel, dodging in and out of the deluge, from one verandah to the next, the compacted coral street already a shimmering river of mud. Overhead wires had eerie flickers of St Elmo’s fire running along them and sudden explosions of blue sparks showered into the air as power surges met transformer boxes, setting them off like Chinese firecrackers.

There was something particularly soothing that night about gaining the safety of our hotel rooms and lying in bed listening to the steady patter of raindrops on the roof as we drifted off to sleep.

| Author Notes | Next instalment - onward, to Guatemala. |

![]()

By tfawcus

We returned to Belize City late the following morning in much the same way that we had come, speeding across the Caribbean in an open boat. What an exhilarating start to the day!

At the TACA check-in counter we are informed that our onward flight to Guatemala has been over-booked and that the airline will be putting us up in a local flea-pit overnight.

One had the feeling from the body language accompanying Wendy's finely modulated response that this was set to be more than just a border skirmish. Words continued to fly until just before the final call for boarding, at which time the manager proposed a compromise. They could fly us half-way, to Flores, and put us up there for the night instead, then take us on to Guatemala City the following evening.

After a rapid discussion of the pros and cons we conceded, but only on condition that we had two nights in Flores, one paid by the airline, the other paid by us. All being finally agreed, we clambered aboard barely minutes before take-off. It would now just remain for us to persuade Air Caribe to re-write our tickets from Flores to Cancún , so that we could use them to fly instead from Tuxtla Gutiérrez, about two hundred miles further west, in the Chiapas region of Southern Mexico, but that was a battle for another day. We had fought hard enough for one day already, just to get this 25-minute flight across the border into Guatemala.

We found El Hotel del Tropico tucked away down a side alley in a street full of mechanical workshops and hardware stalls. Policemen loll against breezeblock walls with sub-machine guns slung loosely from the shoulder, urchins pee in the gutter, buses blare as they cut a swathe through assorted cyclists and pedestrians swaying and swerving in all directions as they go about their daily business. Dusty and hot assail the nose, but really the spice of the place is in the air; a delicious mixture of food odours from roadside stalls mingles with the stench of burning rubber and diesel fumes; a suggestion of over-ripe banana and mango hangs in the background and somewhere just over the wall a sweet scent wafts, fleetingly redolent of frangipani.

The following morning, the hotel minibus picks us up at 8 a.m. to drive us out to Tikal. The excursion is a full day, for the ruins are extensive. They are some 40 miles to the east, beyond the end of Lago de Petén Itzá, and lie in a national park covering more than 250 square miles. The central area of the city spans an area of about 12 square miles. Many of the most spectacular of the ruins were excavated towards the end of the nineteenth century by archaeologists from Europe, most notably the Swiss Dr Gustav Bernoulli in 1877 and the English archaeologist, Alfred P Maudsley in 1881. In the last forty years the work of research and restoration has been continued both by the University of Pennsylvania and Guatemala's own Institute of Anthropology and History.

The road takes us along the southern side of the lake and there are several small villages dotted along its shore. We are told there are three lakes in this region, one of fresh water, the next of salt and the third of sulphur. The lake we follow has several kinds of fish, including white bass, and it is home to a small freshwater crocodile. The crocodile and turtle are much revered in the Mayan mythology, being creatures able to cross the divide from one world into another. Men plod tirelessly along the roadside with huge loads of firewood on their shoulders, held in place with bands running from their foreheads. Women with pads of cloth on their heads balance bags of maize and brightly striped earthenware jars full of water from the well. Small piglets and chickens stray across the fields and road. Barefoot boys race after the bus, shouting and waving their hands. Along the verge hollow ribbed horses and angular cows are tethered to graze and every inch of land that is cultivable up to the very edge of the jungle is neatly planted with row upon row of subsistence crops; predominantly corn but also beans, plantains and a small variety of other vegetables.

As we get closer to the ruins the vegetation thickens. A jungle turkey struts across the road in front of the van. Vines hang down from the trees. Our guide when we get there is a friendly man, not a Guatemalan as it turns out, but a Honduran who learnt his English in a bi-lingual fishing village on the coast. He fled to Guatemala as an illegal immigrant in more troubled times, a status which has now been regularised by the authorities although even after twenty years they still won't grant him citizenship. He is still hoping. Perhaps next year, he grins.

It is clear that he is just as knowledgeable about the jungle plants and wildlife as he is about the ancient Mayan ruins. Our first stop is by an allspice tree. He plucks a leaf and crushes it. The aroma is immediately overpowering. This is not the source of the spice, he tells us, but an infusion of these leaves is a most powerful remedy for the stomach ache. Well, that could come in handy! Bunches of unripe berries hang higher up, a month or two from harvest.

In amongst the coarse grass below there are patches of mimosa with their tiny mauve balls of flower and comb-like leaves that shrink away and close to the touch. An army of leaf-cutter ants crosses the path carrying sawn-off pieces aloft, some three or four times their own size, down into holes in the ground. These are the expert gardener ants. On their beds of leaf mould a fungus will grow, and it is this which forms the diet of the industrious insect and its larvae. If all Guatemalans were as hard-working as these ants, our guide observes, we would be a rich country without worries or care.

Next we pass a chicle tree whose sap between the bark and the trunk is farmed like rubber, to the eternal benefit of the chewing public and, of course, the enterprising Mr Wrigley. Above it. wheeling in lazy circles, there is a swallow-tailed falcon and then, round the next corner suddenly, the steep sides of a burial mound. Overhead in the dense canopy of the rain-forest, a chattering spider monkey swings away through the trees, much as he might have done two thousand, seven hundred years ago, when the first of these huge stones were being hauled into place.

We have arrived.

| Author Notes | Next instalment: "The Kingdom of Lord Chocolate" |

![]()

By tfawcus

Tikal conceals layers of history. Its fortunes waxed and waned under a succession of rulers between 700 BC and 700AD, sometimes rising on the tide of fortune, sometimes sinking in the ebb and flow of internecine strife. The spectacular ruins which stand there now date mainly from around 700AD when, as the guidebook says, a renaissance occurred. A new and powerful king, glorying in the name Ah Cacau [Lord Chocolate], ascended the throne, restoring not only the military strength of the city but also its primacy as the most resplendent city in the Mayan world.

Most of the ruins there today date from that time. Awe-inspiring temples rise up, between one and two hundred feet from the jungle floor; steep, square structures aligned with passage of the sun and precisely measured to carry the echo of voices and music effortlessly over the space between them. Some effort of the imagination is required to see them as they might have been; painted according to a complex code in which white, yellow, red and black signified north, south, east and west, the four cardinal compass points; reverberating with of the sound of music; alive with the splendour of ceremonial head dress, jaguar and quetzal masks and flowing robes.

Today the jungle has reclaimed them, stripped them back to grey, decked them with vines and creepers and made their crevices home to small exotic birds. Way back on the far side of the complex we reach what is unromantically classified as Temple IV, the mightiest structure of them all, soaring two hundred feet towards the sky. From the base it looks like a small, steep hill. It is possible to clamber up, sometimes holding onto tree roots, sometimes assisted by small sections of ladder until reaching the stone steps up to the roof comb.

The view from the top is spectacular, miles in every direction across a jungle canopy draped in swirling mists. Black vultures wheel and soar over the tops of other buildings which rise up out of the ancient city complex. Below, like ants, other tourists climb, pausing both for breath and to photograph and feed a cheeky cousin of the raccoon, named quatromundi by our guide. On our way back he stops to show us the fruit of the breadnut tree, small and green. He peels off the outer pith to expose a nut about the size of a kidney bean. These, he says, were roasted and stored by the ancient Mayans, then pounded up to make a flour for cooking, much more nutritious than wheat or corn. Granaries full of them were uncovered during the archaeological digs.

We finish our tour at the Great Plaza, where Temple I, the Temple of the Grand Jaguar, stands facing Temple II, its twin, 100 yards across the plaza. We arrive there at the approach of a tropical storm. The sky behind the Temple of the Grand Jaguar blackens as a solitary black vulture settles on its top, flapping his ungainly wings. An unearthly stillness fills the air and for a moment we feel the mystic power of this ancient place as time stands still. Then suddenly the magic is broken. The sky is split by jagged lightning forks. Thunder rumbles, echoing and re-echoing around the ruins, and the rains begin as we scurry back to the shelter of our minibus.

We have until mid-afternoon the following day before our onward flight to Guatemala City. In the morning we walk just a few hundred yards to cross the narrow causeway from Santa Elena to Flores, a town of some 2000 inhabitants built on an island at the western end of Lago de Petén Itzá. Women sit at the edge of the lake, pounding their washing on a stone. Nearby a solitary youth has carefully stripped to his underpants to do his washing. As each item is cleaned he wrings it out and puts it back on again. Within half an hour he will be dry. Further down the causeway a young boy sits cross-legged in the water, chasing minnows with his hands, a red plastic bucket beside him, just in case.

We breakfast in the company of a small black puppy in a restaurant overlooking the lake. He is clearly glad of the company and to attract our attention he growls playfully and attacks trouser legs, handbags, shoelaces and anything else that we are careless enough to leave at his level. Before long the meal arrives; scrambled eggs, black bean mush and fried bananas. Yum!

The rest of the morning we browse around the town. I buy a little wooden armadillo for Anna in the giftshop attached to the museum. It is the one on the shelf with a strange almost quizzical expression on its face which sets it apart from its fellows. I’m not your ordinary run-of-the-mill armadillo it seems to say. I’m different. It reminds me of the story of Painted Jaguar and the Beginning of the Armadillos.

‘Can’t curl, but can swim -

Slow-Solid, that’s him!

Curls up, but can’t swim -

Stickly-Prickly, that’s him!’

But the tortoise learns to curl and the hedgehog learns to swim, they share the hedgehog’s prickles and confuse Painted Jaguar most dreadfully.

‘But it isn’t a Hedgehog, and it isn’t a Tortoise. It’s a little bit of both, and I don’t know its proper name,’

‘Nonsense!’ said Mother Jaguar. ‘Everything has its proper name. I should call it “Armadillo” till I found out the real one. And I should leave it alone.’

We go to the post office in the town square to buy stamps and post some cards. It is a wooden desk in a room otherwise full of piles of rock and mosaic from the Tikal ruins. A young girl takes the cards, carefully sticks two huge stamps on each, rummages around in the desk drawer to find a small machine to hand frank them and then tosses the cards into a hessian sack on the floor. What marvels of modern science, we wonder, will speed them on their way from there, across two continents and an ocean?

The view from the town square is stunning, across tiled rooftops to the whitewashed bell-tower of the church. Then to the lake beyond, palm-thatched huts on its shores, fishermen in dug-out canoes silhouetted against the sun and larger passenger boats with white canopies plying their trade from shore to shore, all reflected in stipple and shimmer, sun dance brushstrokes on the water.

We, too, must be on our way. Tourist butterflies in this timeless land.

| Author Notes |

Quotations are from Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories

The next stage of our journey takes us to Guatemala City and thence to Antigua, more properly called the most Noble and Loyal City of St James of the Knights of Guatemala, a most remarkable place and one of the highlights of our adventure. |

![]()

By tfawcus

I have walked Antigua from one end to the other, from one side to the other, along its cobbled streets and high narrow pavements. The journey in each direction takes less than half an hour, even when time is taken to loiter in open doorways and glimpse the sun-drenched courtyard gardens hidden behind each wall.

We are lodged at the Hotel del Carmen, two blocks back from the street sellers and shoe-shine boys of the city's bustling Central Park. The guidebook tells me that the famous fountain there was built in 1738 and I wonder ... has anything been built since that time in this most special of places?

Founded in the sixteenth century, the most Noble and Loyal City of St James of the Knights of Guatemala was the seat of government. Then in 1773 a great earthquake caused the capital to be transferred to the ugly sprawling metropolis of Guatemala City. With funding and power removed, La Antigua Guatemala was soon forgotten and became locked in a time warp, 5000 feet up on a small plateau, ringed by towering volcanoes and protected by its isolation. I have seen nowhere even remotely like it anywhere else in the world.

Like most cities, it is best seen at dawn, when zephyr breezes begin to wash away the silence of the night. I hear a thin metallic chime of a distant bell strike five. Cocks crow, one to another across the valley. There is just enough light to see the whiteness of the page, the black marks being made upon it, but not to distinguish the individual words of the song. So it is with the town, from the edge of this rooftop garden. To the southwest, a stone's throw away, there stands the bare silhouette of the Catedral de Santiago, lit yellow by street lamps. Behind and to its left loom the shadowy slopes of Volcán Agua, towering ten thousand feet and more; silent sentinel of the south. This one is a tame giant, its fires quenched by a dark and subterranean lake. Farther to the west there are two more distant peaks; below them lie thin wisps of grey mantilla lace, a swirl of morning mist. A thin dark sulphurous plume rises from the left, more distant peak. Sometimes it is said that at night the jagged cone of this one, Volcán Pacaya, glows red in the dark - but it is far enough away and does not threaten the city or its people.

A veil shrouds the silvered gibbous moon as the first blue-grey light of dawn brings meaning to my page. A black cat scampers along the rooftop tiles, too busy to bother with a lone stranger invading her domain. Behind me there is a sudden crackle of fireworks; a second volley, more distant, answers from the west. It is Saturday morning. Do they salute the dawn? Or are there revellers still at large in this awakening town?

Now, at 5.25, the twilight magic strengthens. There is the first rumble and clatter of morning traffic on the cobblestones. On my right, rises the solid rectangular shape of the roofless Iglesia El Carmen. The medieval tiles of the three or four low pitched roofs intervene. Six round windows spaced evenly high up in a nave wall now frame the speckled pink of dawn. Four ornate columns decked with ferns and moss define this church's entrance on the eastern street. Behind, below its outline and to the left, the shadows of two palms stand side by side. Beyond, directly to the north, a low tree covered hill defines the city boundary. Near its top a cleared patch of green field, perhaps a hundred yards across and fronted by a low stone wall, has at its upper end the massive outline of a wooden cross which guards this sleeping city. Among the lichen covered terra cotta tiles, here and there above chimneys there rise small square cupolas, whitewashed and domed.

The hour of six chimes thinly from the ochre tower of Iglesia de Santo Domingo, echoing across the valley, soon to be answered by a clatter of bells from the opposite, south-eastern corner of the town. Now the lone angelus. Iglesia de Santa Lucia is calling its faithful to prayer.

Below me a courtyard garden wall supports vivid sprays of bougainvillea and spindly bushes covered with jaundiced limes. The first rays of sun touch the garden in which I stand, with its borders of iris, rose and fuchsia, its ragged splashes of plumbago blue and oleander pink; its geranium and fuchsia in painted pots. The sky behind the main plaza is silver now between the volcanoes. Volcán Pacaya sends up a small black mushroom belch into the middle distance every three or four minutes; just enough to remind one that the giant only sleeps, he is not dead.

Steps lead down to the hotel balcony, with its black wrought iron rails surrounding a Moorish internal courtyard, typical of so many of the houses here. Already the first guests are beginning to seat themselves for plates of fresh tropical fruits and steaming pots of coffee, with which to start the day. In the middle there is a fountain, onion shaped and painted with rough brush strokes of Italian blue. Broad leaved green aquatic plants grow in its tier of dishes, splashed by a slow-welling stream of water which cascades into the pool below. The floor is tiled in terracotta. Four raised garden beds are divided one from the other by curved stone seats forming alcoves, each with a small round table with white table cloth and two cane chairs. Between the columns, brick red arches match the floor tiles. The flower beds are filled with palm fronds and ferns, and vines trail down the fluted columns softening their line. Sun streams in through a glass roof, making dappled patterns where it falls. How could I not feel centred and at peace as I join my travelling companions? Breakfast is served, and I will soon be ready for the adventures of the day ahead.

Our tour of Antigua with Elizabeth Bell is fascinating. She is an extraordinary woman. Her tours and books help to fund community projects, and her energy and advocacy broker links between the common people and their local government. She is an expatriate American who has lived in Antigua since she was fourteen years old. It is, in every sense, her home. The people are her family.

We start at the town hall, where she notes two women waiting patiently to register the births of their new-born babies. Recently, with the new government, this has become much easier. It is but a small example of the changes. Before, they would have been given the run-around, told to wait all day, to come back again tomorrow or next week, fobbed off until at last they gave up the attempt. Their children would have become non-persons with no official existence, no rights to passports, education, anything. Now things are changing. Opportunities for education grow in this land where the literacy rate is around 5%. Grievances that in the past dared not be voiced, are now heard.

Across the square is the cathedral of Santiago. The façade and front section are still intact. Beyond the transept lie the ruined remains of the rest, left gradually to decay for two hundred years or more. Now the columns and arches are being carefully restored, floors renewed, walls repointed and plastered. The roof will not be mended for this is to be a community space. Sunshine will flood in during the day. At night it will be open to the stars and moon. A space for youth theatre. A space for the people.

We enter a breathtaking courtyard across the street. The covered archways lead us through to a museum of jade and to a factory in which the stone is cut and polished and fashioned into jewellery. The profits help fund the college housed in the rest of this magnificent building. This is the story of a people who have joined together to help themselves, to help each other, and the small jade ring, which I purchase as a gift for Wendy, will always hold within its depths a reminder, some faint memory of them.

This ancient city leaves an indelible impression. We shall be sad to leave.

| Author Notes | Next instalment: Panajachel, on the shores of Lake Atitlan |

![]()

By tfawcus

I wish that I could write of Atitlán's

volcanic peaks, and depths unplumbed as yet,

whose mirror caught at dusk a silhouette --

a sacred breath of life - the lone toucan

that flies between the spirit world and man,

defending all from evils that beset

the simple souls who daily cast their net,

poor fishermen, subsisting as they can.

But one small boy, Ernesto, fills my eye -

a tin box slung behind - his carapace -

whose cheerful cry of "Shoeshine!" hides his sweat

for patrons with a quetzal spare, to buy

a shoeshine mirror of his earnest face,

and ease the burden of his family's debt.

When my daughter met Ernesto, she asked him what his dream was. He thought for several minutes as if he had never considered the possibility of dreams. Eventually he said that one day he hoped to become a driver, a chauffeur. That was the biggest dream he could think of.

This story is, for me also, a dream, some twelve years into the future, not in my time but in my daughter's. When I was in San Pedro, Ernesto was yet to be born, for he was eleven years old when Anna spoke with him, and he was already the man of his house. Six months earlier he would have risen at dawn, done his chores, taken up a satchel of books and gone to school - but then his father fell sick.

Now he rises at dawn, slings a tin box over his shoulder, gathers in his arms a small wooden stool and heads down to the jetty, and he waits for a boat to carry him the three miles from San Marcos on the northern shore to San Pedro in the south, where he will work until dusk as a shoe-shine boy.

The decorations on his tin box are ghosts, except that they wear shoes and each carries a tin box - or is it a satchel? It is hard to tell. They are also decorated with ghosts, too small to see with the naked eye, the ghosts of what he might have become.

He walks the streets of San Pedro alone, asking people if he can shine their shoes.

"Only 2 quetzals, señor."

On a good day he earns 20 quetzals, a little under US$3. However, there are not many good days.

Atitlán has majestic, towering basalt peaks. There is mystery in its watery, unplumbed depths. There is pragmatism rather than mystery in its people, who live on the edge of the lake. They are numbered among the world's silent majority, who live also on the edge of starvation.

If they are lucky, they are shielded at night by the sacred toucan who holds shut the gates of the spirit world and keeps them safe from the living dead, so that they may sleep in peace and gather strength for the toil that is their lot on each new day.

I have inserted this slight detour from my travels, because it is so closely aligned with the story of Elizabeth Bell and the two women at the town hall in Antigua, waiting patiently to register the births of their new-born babes, to save them from the fate of becoming non-persons with no official existence.

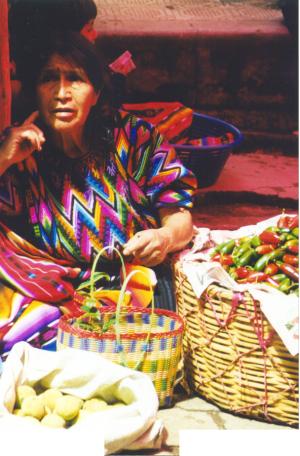

In 2011, Anna was living in Guatemala for a time, undertaking a photographic project with the Global Fairness Initiative (GFI), an American non-profit organization, based in Washington DC. She was documenting the informal sector living in Guatemala in a project called 'The Voiceless Majority'.

In explaining the project, she mentions that more than seven out of ten jobs are created in the informal economy in Guatemala and that informal workers do not have access to government benefits such as social security or health care, are highly exposed to market fluctuations, and broadly lack physical and financial security.

She says that informality creates an alternative or shadow economy, which is not recorded in macro-economic terms, and that it is one of the major development issues of our time. When you ask people what poverty is, an image jumps into their head. It is the destitute farmer on a drought-ridden plain, standing outside a dilapidated home, or it is the tattered rag picker squatted on a busy street in Dharavi. Ask the same about food insecurity or gender inequity and an image comes to mind. But ask about informality and there is no image, thus no story, no context, and no response to drive action.

The Voiceless Majority photography project was aimed at providing an image and story on informality by exhibiting the experience and "face" of the informal sector. It consisted of a collection of photographs of the lives and livelihoods of six informal sector workers from Guatemala. For each series, audio recordings of the actual subjects were broadcast to provide a combination of "face" and "voice" that tells the story of an informal worker and thus personalizes "informality."

Whilst I was merely a tourist, a voyeur if you like, my daughter is an activist and I am proud of her.

| Author Notes |

Image copyright Anna Fawcus 2011, one of a series taken for The Voiceless Majority project. Further information and photographs can be found on her blog. The page concerning Ernesto Alfredo is at http://www.annafawcus.com/blog/the-voiceless-majority-ernesto-alfredo

I wrote the poem that starts this part for my daughter in 2011. This version has been heavily revised as the rhythm of the original was diabolical in places. It is, for those of you who are interested in such things, an Italian or Petrarchan sonnet. The next section of this travelogue will continue with my visit to the shores of Lake Atitlan in 1999, which was, by comparison, incredibly banal. |

![]()

By tfawcus

From Antigua, we drove up through the Guatemalan highlands to Panajachel, on the shores of Lake Atitlán. It is a journey of about two and a half hours through rugged mountain country. A bank of low cloud hangs in the valleys and distant storm clouds tower behind the lush green slopes of volcanoes. The villages are ramshackle, poor and mainly of breezeblock with rusty iron roofs. In contrast the people are colourful and wreathed in smiles, despite the brutal hardness of their lives.

Almost all the women wear traditional Mayan costume; some of the men too, although western-style jeans and shirts are more common. Acts of physical endurance beggar belief. Men set out for the hillside with iron mattocks, two feet across the blade, with which to tame the land. Sheer slopes, 60° or more, well beyond the capacity of any machine or beast of burden, are neatly terraced and planted with maize. These are a small, stolid people. We are as giants among them, yet I doubt I could even lift some of the tools with which they wrest their living from the land.

I saw one man walk by the side of the road with six timber planks vertical upon his back. They overshadowed him. It was a fearsome load. Before long he veered off onto a narrow, precipitous track which wound ever upward to the terraced ledges clinging to the side of the mountain which he farmed. Women routinely passed us by with earthenware jars upon their heads. I would estimate the jars to hold three, maybe four gallons of water. Yet the women walked with all the poise and grace of Swanson Street models, showing off millinery designs for the Melbourne Cup.

The last few miles into Panajachel are a succession of hairpin bends descending steeply from the mountains to the sparkling mirrored surface of Lake Atitlán. Some twelve miles long and six miles wide, the lake itself is a collapsed volcanic cone. It plunges to a depth of almost 1000 feet. Surrounding the lake are three huge volcanoes, ranging from 9,800 to 11,600 feet. Their summits are almost permanently covered in wispy caps of cloud. As seems to be the case everywhere in Guatemala, their slopes are terraced and planted with neat rows of maize, from the lakeside almost to their very peaks. On the final approach to the town the mountains rise vertically, towering above the road. A spectacular waterfall cascades hundreds of feet down a gorge before disappearing under the road, where it empties into the raging torrent of the Panajachel River.

We scarcely have time to leave our bags in the Hotel Dos Mundos before Wendy has arranged a trip for us by boat across the lake, calling in at San Pedro La Laguna where we are to have lunch at a lakeside restaurant. I bravely partake of the local black bass, heavily smothered in fried onions and, much to everyone’s surprise, survive to tell the tale.

From there we go south across the lake to Santiago Atitlán, a small town squeezed between the towering volcanoes of Tolimán and San Pedro. Women in brilliantly coloured huipiles meet the boat, laden with woven cloth for sale. For quarter of a quetzal they offer to let us take their photographs. When there is no sale their sunny smiles give way to scowls and a silent curse, presumably to Maximón, a local deity who seems to be an amalgam of ancient Mayan gods, the Spanish conquistadors and biblical Judas, despised in other highland towns but revered here in Santiago Atitlán. Each year he resides in a different house in the town where he receives offerings of candles, beer and rum. During our visit we are led to a shanty dwelling in a backstreet near the top of the town where Wendy, Jeanette and Matthew pay 2 quetzals apiece [about 40 cents] to commune with the god and receive his message. They are somewhat reticent when it comes to divulging what this message is!

From there, having browsed the many shops selling woven cloth and other handicrafts and souvenirs, we make our way to the huge white church which dominates the town. Its walls are lined with wooden statues of the saints which are newly adorned each year, in robes woven by the women of the town. The pulpit is intricately carved with an images of Yum-Kax, the Mayan god of corn and of a quetzal bird reading a book. Near the door, there is also a commemorative plaque to Father Stanley Francis Rother, a missionary priest from Oklahoma, much loved by the local people, who was murdered on the steps of the church in 1981 by an ultra right wing death squad. As we leave the church, a huge black cloud hangs over the mountain like a funeral shroud.

We return to the boat and set course through the reeds of a bird sanctuary island on the lake towards San Antonio Palopó on the eastern shore. Time is getting on and so we do not disembark here. There is a fine view of the place from the water and its streets look very steep. On this side of the lake we pass a small volcano which our boatman tells us is known as the Mountain of Gold. Legend has it that years ago the Mayan priests threw all of their treasures into its mouth to save them from the Spanish conquistadors. Our boatman assures us that he himself has dived on that edge of the lake and that there are subterranean passages into the mountain where ancient shards of pottery have been found, pointing to the truth of the tale.

Our final stop before returning to Panajachel is at a rocky outcrop on the eastern side of the lake. Hot springs bubble here and steam rises from the surface of the water. We ask our boatman why the rocks above have all been wound with barbed wire. He points up to the left, to the palatial holiday home of one of the 2% of Guatemalans who own 90% of the country’s wealth. The owner wants to dissuade people from coming here to bathe in this part of the lake which borders his property, he says. There are many such houses scattered around the shores of the lake; most are only accessible by boat or helicopter. They are the lavish holiday villas of the super-rich - a glimpse of the other side of the coin.

![]()

By tfawcus

By the time we got back to Panajachel Tom was far from well; his chest was in a bad way. Being drenched in a couple of sudden local rain squalls had made matters worse, so we returned to the hotel early and put him to bed.

That evening, sitting on the verandah outside my room as the sun went down, I watched a tiny hummingbird less than three feet away, hovering in the white trumpet of an ornamental tobacco plant. Such fragile and transient beauty! This country is full of surprises.

Perhaps one of the most human of these is the anecdote of Jeanette's lost credit card earlier that same afternoon. During a visit to the ATM she lingered a few moments beyond the twenty seconds allowed, whilst discussing with Wendy the exchange rate and how many quetzales she would need to withdraw. In this brief time the machine swallowed her card, leaving a message on its screen that she could pick it up from the bank. However, it was Saturday and the banks were closed until Monday, by which time we would be gone.

Wendy recounted this minor tragedy in Spanish to the proprietors of the shop next door. They were quick to suggest she went to a nearby luxury hotel, whose owner's son used to work in the bank; the Hotel Posada de Don Rodrigo, on the shore of the lake. Alas, he could not help. His son had now moved to another branch. However, he said they would do what they could. His wife then climbed into her car and drove eight or ten miles through the mountains to a nearby town where she knew one of the bank staff lived. An hour and a half later there was a knock on the door of Jeanette's room, two friendly smiles and a bank card reclaimed. No thought of recompense. Gratuitous acts of kindness to travelling strangers in distress. And this in an area where the guidebook had warned of the possibility of random attacks on lonely country roads, robbery, rape and the murder of tourists.

On Sunday morning we left Tom at the hotel to recover and caught a bus up to Chichicastenango in the Department of Quiché. It was about an hour's drive winding through steep valleys, up and down mountainsides, to this beautiful little town tucked away in the hills. There is a bustling market on Sundays and we arrived just in time to see one of the confradias, or religious brotherhoods, holding a ceremony of slow rhythmic dance on the steps of the church before setting out in procession through the town amid clouds of incense. Also on the steps of the church there were flower sellers, women in traditional costume with huge bunches of gladioli and chrysanthemums.

The narrow streets crowd in, with stalls on every side and a relentless tide of people ebb and flow along the cobblestones paths between. The fruit and vegetable market in the town square has every sort of simple household necessity; pots and pans, brushes and besoms, mattocks and hoes, soaps and spices. There are great piles of dried fish, mounds of sweet green oranges and pink bananas, sacks of beans and maize flour, feathered chickens in bundles hanging upside down from poles and scores of diminutive bustling ladies in brightly woven huipiles, all elbows and shopping bags, racing to make their bargains with gap-toothed smiles before the day is done. Time is short. The flotilla of yellow local buses which brought them in at dawn from scattered outlying villages will all leave again by mid-afternoon, laden with people hanging out of the windows and clinging to chromium bumper rails, their piles of produce balanced precariously on impossibly overloaded roof racks.

Here in Chichicastenango we make our own small purchases; plaited shoulder bags, woven cloth for cushions, a mirror framed with worry dolls, and other souvenirs. By lunchtime we are ready to retire two blocks east of the plaza, to the Hotel Santo Tomás. Steps rise steeply from the street to this oasis, a haven from the bustle and heat of the marketplace. Through its doors lie mosaic paths to a lush garden courtyard with colonial fountains. There are rails among the foliage upon which strut huge scarlet macaws that squawk and eye passing strangers with disdain. Behind, under an archway beyond, a Mayan sits, playing haunting mountain melodies on a xylophone. The rich sonorous timbre of the zericote wood floats upwards through the garden and along the patios with their cane chairs and lazily revolving fans, where weary travellers rest. That's us! We cool ourselves with tropical fruit shakes in tall glasses while tempting delicacies are prepared for lunch.

Around mid-afternoon the bus returned to take us back to Panjachel. It clattered down cobbled streets to a small hotel on the outskirts where there was one more passenger to pick up. Here a small incident occurred which sticks in my mind. Three soldiers stood by a roadside stall, sub-machine guns slung loosely at the shoulder, casting a shadow on this otherwise peaceful Sunday afternoon. The sergeant had in his hand a leather whip with two knotted thongs; the sort which I had seen used by Mayan peasants along the roadside to gently flick the flanks of donkeys, heavy laden and loitering along the way. Clearly the use he had in mind was different as he demonstrated to his two subordinates a variety of cuts and lashes, each adroitly executed with a flick of the wrist. Then he picked up a claw hammer from the stall, carefully felt for a balance point along its shaft and, using the back of one of his colleagues' hands to demonstrate, mimed delicate crushing blows to finger joints and knuckles. The three faces were impassive, devoid of emotion. I had the impression that they would not have greatly cared who their next victim was, or whence he came. Cruelty for them was a macabre art form, insensate and beyond reason. Although the sun shone warmly through the window of the bus, I found the air grow cold and could not suppress a silent shudder.

This incident grimly foreshadowed the latent dangers of the next stage of our journey, up the west coast of Guatemala and across the border to San Cristóbal de las Casas, at the heart of the Chiapas region of southern Mexico. Only a few years earlier, an extremist left-wing group, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, had been active in the area, taking control of key infrastructure and attracting much publicity in the world press. Tensions still exist not far below the surface in this part of the world, as we soon discover.

![]()

By tfawcus

The final stage of our journey back to Mexico is a hundred and fifty miles by road in a privately chartered minibus, north along the Interamericana Highway to the border town of La Mesilla.

Highway is perhaps a misnomer. The road rises up, twisting and turning through the Guatemalan highlands, and clinging to the sides of mountains as it threads its circuitous path towards the border. Mostly it is metalled but in places it disintegrates into potholes and even sections of dirt track filled with broken rock, where the road has been swept away by earthquake and flood.

As has been the case throughout Guatemala, every inch of land is hand cultivated, with neatly terraced mountain slopes rising up behind small towns nestling in the valleys. The village people and field workers make bright specks of colour on the hillside with their traditional hand woven cloths, as they toil among the spikes of corn. For the last twenty or thirty miles we follow the course of a wide and muddy torrent which splashes, foaming over jagged boulders strewn about the riverbed that leads us to the border.

Formalities leaving Guatemala and crossing into Mexico are slow and protracted. Papers must be filled in, then pored over by officials before they receive the purple impress of a stamp. A few quetzales change hands on one side of the border; a few more pesos on the other. Eventually we are cleared to drive in a collective taxi the two miles across no-man’s land to Ciudad Cuauhtémoc on the Mexican side. Here we change to another minibus which takes us fifty miles farther on, to Comitán.

Three more times on the Mexican side we are stopped at military road blocks, spaced about five miles apart. Our passports are minutely examined by the sergeant while soldiers who look no more than fifteen or sixteen years old peer in through windows and poke amongst our suitcases with the butts of their rifles. Other watchful eyes look out from sandbagged machine gun emplacements fifty yards farther up the road, where a lever stands ready to raise spikes across the road should anyone decide to make a dash for it. Our driver says they are looking for illegal immigrants from El Salvador and searching, too, for drugs.

Throughout Chiapas there is clear evidence of a strong military presence. Perhaps it is an aftermath of the revolt five years earlier, in 1994, by the Mayan Indians of this region, in which armed rebels of a group calling itself the Zapatista National Liberation Army seized several towns and villages, kidnapping officials and destroying government offices. Resentment still runs high, with the Chiapans having good reason to mistrust the corrupt central government up north in Mexico City, although there is evidence that concessions have been made and an uneasy peace agreement reached.

At Comitán we change again for the final fifty miles into San Cristóbal de las Casas, at the heart of the Chiapas region of southern Mexico.

San Cristóbal has something of the architecture of La Antigua Guatemala, but on a larger, less intimate scale. The people are less open, more sullen and seem distrustful of foreigners. There are some magnificent churches and street markets here and it is easy to let the time slip away as we wander. Half a day is lost in the airline office of Air Caribe, negotiating the change in our tickets back to Cancún . The staff are friendly and most obliging, but they have to make many phone calls to head office before we are eventually able to get the tickets reissued. Here, as on so many occasions in the past ten days, Wendy’s ever more fluent Spanish is an invaluable tool in helping to resolve the muddle and to find an acceptable solution for us. But it all takes time.

Perhaps the most interesting part of our stay is a visit to Na Bolom, a house on the outskirts of the town. For many years it was the home of a Dutch archaeologist, Frans Blom, and his wife Trudy, a Swiss anthropologist and photographer who died here in 1993 at the age of 92. These two shared a passion for the Chiapas region and its Indians, and worked tirelessly to improve their lot. The house is full of photographs, archaeological and anthropological relics and books, but it is more than just a museum; it is also a research institute dedicated to continuing their work in the region. It takes a long walk down semi-deserted streets well away from the centre of town to find it, but the search is well repaid.

Amber is one of the specialities of the region, formed some 25 to 35 million years ago from the sap of the Courbaril tree and creating deposits in present day Chiapas. For years it has been used for medicine, the magic arts and religious rituals and has been considered to be an amulet for protection and good luck. It is with this in mind that at the very last moment I buy a bracelet and broach for Wendy, both set in curiously wrought Mexican silver and having deep within their hearts the fossilised remains of ancient life.

Soon afterwards, we board a bus to cross the mountains to Tuxtla Gutiérrez for our flight back to Cancún. Although only just over fifty miles, it is a two hour journey. At times we are driving through clouds, as they swirl around the mountain tops and hang over the valleys. When the clouds are like this, our driver tells us, it means that there will be much rain in the afternoon. He is not wrong!

Shortly after our arrival at Tuxtla’s airport the heavens open. For nearly an hour there is a torrential deluge which obliterates the view to the other side of the street. Ten minutes before we are due to board, an announcement is made over the P.A. in Spanish, to say that the airport has been closed. Our flight has been diverted into the larger Aeropuerto Llano San Juan, sixteen miles to the west. Wendy soon has us bundled into taxis which speed us through the outskirts of the city. In some places the roads have become raging torrents of orange mud and it seems doubtful that we will get through. However, we make it, and eventually get airborne for our flight via Villahermosa and Mérida, arriving in Cancún soon after sunset.

To our relief we are met at the airport and driven to the ferry terminal at Puerto Juárez for the twenty minute crossing to Isla Mujeres. There to meet us on the jetty with a huge smile of gold-capped teeth in a nut-brown wrinkled face is Fidel with his tricycle luggage cart. He escorts us to our condominium, two or three hundred yards west along the seafront, overlooking Playa Norte, better known locally - he tells us - as Naughty Beach. I wonder why?

The rooms are luxurious, air conditioned and well furnished with all modern conveniences. The balconies overlook a floodlit swimming pool, the beach and, further out beyond the reef, the distant lights of the mainland. As we sink down into comfortable beds it seems that our adventure is over at last.

The next morning, I wake early to that strange quiet that precedes the dawn. The beach is deserted but for a few Mexican pi dogs and a line of small wading birds bobbing and strutting at the edge of the surf. Sub-tropical breezes tug at coconut palms in the coral sand and dark wisps of cloud scud across the moon’s thin crescent in the east, as the morning star begins to fade, giving way to salmon and azure hues creeping across the sky. A growing chatter and trill of hidden birds heralds the arrival of the new day on this northern shore of the island, a sheltered lee. Waves break gently with a rhythmic murmur, and a solitary frigate bird spills the morning breeze from under the sharp angular outline of a wing as he dips and weaves to stay still.

This is my first taste of Isla Mujeres, the Island of Women, which is to be our home for the last week of the holiday. Legend has it that Caribbean pirates kept home comforts here while they plundered passing traders. Where are the pirates now? They have become the traders, in rows along the streets, their stalls brimming with bric-a-brac, T-shirts, wrought silver trinkets. They sell Mayan lace and woven blankets, wood carvings, and trips to the reef, to ancient ruins and to Cancún’s hotel strip.

‘Almost free!’ they lie, enticing another boatload of tourists from the mainland to part with precious dollars. Every half hour the fast boat comes with its new cargo of flesh oozing from floral prints, eager after twenty minutes on the high seas for group adventure, neatly packaged with free gifts and unmissable offers of three for the price of four. Traps for the unwary.

“Just 27 pesos, señor. I tell you what - I give you a special offer - three for 85 pesos - my best price. Come in and look around. See what you like.”

For our part, we sunbathe, swim and sip exotic cocktails in Charlie’s Bar, while casting sidelong glances at the nubile bodies on Naughty Beach and enjoying the feel of cool sand between the toes.

Towards the end of our stay we make an excursion back to the mainland to visit Chichén Itzá, the most famous and best restored of Yucatán’s Mayan sites. It is well that I should finish at Chichén Itzá for we came to Central America to follow the Mayan route, and this is a fitting end to it. The journey by car from Cancún is between two and three hours. We are lucky that it is a damp day with steady drizzle for much of the time. Blazing sun at the height of the day, combined with high tropical humidity could have made such a journey refined torture.

Unlike Tikal, Chichén Itzá is a major tourist destination. It is much more accessible, the ruins are far more recent and in better condition and consequently the whole place is overrun by visitors. Despite that, one cannot help but be impressed. People talk with much awe about the incredible alignment of these buildings to chart the course of the heavens, to divide the year into seasons based on the passage of the solstice, and of the ingenuity of the ancient race who devised our three hundred and sixty five day calendar. However, below the surface, one also feels the sweat and toil of human misery; those generations of conquered slaves upon whose bones and blood this place was built.

What now remains? A horde of visitors scrambling over the stones. High in the trees above the temples there is the curious click of the mot-mot bird, whose pendulous tail beats out time, in mockery of the faded magnificence and crumbling ruins of this once mighty civilisation.

It seems appropriate to finish with a short poem, and - of course - to thank those of you who have travelled with me for some or all of this Central American journey, these rambling reminiscences of an old man!

Chichén Itzá