![]()

By Sis Cat

“If anything ever happen(s) to me . . .

You are to come and get the Poetry.

These are very, very important.”

--Fred Wilson’s letter to his son Andre,

December 28, 1985

“Is there more to the story?”

I pressed my ear to the phone, waiting for an answer to a mystery. My mother’s voice, already fading in her illness, traveled through land lines from Southern California to Northern California. In her Texas drawl, she whispered, “There is, but it will have to wait for another time.”

Pulling back from the wall phone in the kitchen where dinner simmered, I retreated from interrogating my mother. My father, Fred Wilson, had died ten weeks earlier without telling me what happened between him and mother. Whenever I visited him in Albuquerque, he stood in his potter’s apron, splattered with clay, his face Sphinx-like. Now that he died, I feared the answer died with him.

I still had one parent left—my mother. Half of a story is better than none. When I visited her in June 2012 to scatter my father’s ashes at his childhood home, I stepped back when I saw her for the first time since that February. She covered her goiter with a scarf around her neck and wore split shoes to ease her swollen feet. Given that my parents had divorced forty-two years earlier, my mother’s deterioration after her ex-husband’s death spurred me to ask the question I always wanted to know: “Why did Fred divorce you?”

Her bloodshot eyes darted, and then stared at me. Her nose dripped. “He didn’t divorce me. I divorced him. I started the proceedings.”

Over the next hour my mother confessed like a woman who knew she was running out of time. Even when I returned to the Bay Area, I called and peppered her with more questions, not only because I wanted to know the truth, her truth, but because I sensed I was running out of time. When she told me over the phone that I will have to wait another time for her to finish her story, I backed off. A part of me resigned to never knowing everything that transpired between her and my father, but I had to respect my mother’s wishes not to press further for more information. A couple of days later, in the wee hours of a Sunday morning on July 8, 2012, my mother, my storyteller of one thousand and one Texan nights, Jessie Lee-Dawson-Wilson, died without telling me the end of her story.

I caught the first flight to L.A. Monday morning.

Until I saw my older brother, Terry, I had thought it was impossible for an African American man to look gray. Our mother's death had drained the life from his face. Tears rimmed his eyes. He stood in the doorway to our mother’s bedroom like an undertaker at a funeral parlor. His hand motioned to the bare patch of dirty green carpet by a quilt-covered bed. “I went into her bedroom and she was on the floor. It looked like she had been praying and fell over. I touched her and she was already cold and beginning to stiffen.”

Entering the bedroom where our mother died, I thought, "I am grateful that I was not the one to find her body, because I would be unable to function with that image etched in my head. I must stay focused on the tasks ahead."

I looked around. Books and papers, poetry and writings covered every conceivable shelf and surface in the room. Even before the paramedics arrived to pronounce her dead and move her body, her room was a mess. “Hoarder,” I thought, embarrassed that others saw this room.

When she ran out of shelf space, she stacked more papers and books on her bed along the wall so that she only slept on half a bed, as if her body was another figurine on a shelf. Whenever I visited, my mother would clear off her bed and make her room presentable for me to sleep while she slept on the living room sofa. None of my siblings who rushed to her apartment wanted to sleep in her room after she died. I proceeded to clear her bed for myself one sheet of paper at a time.

My hands found a typed poem she wrote forty-two years earlier titled “Oblivion.” My lips moved as I read the opening lines,

If I could live in another world,

Or have another life,

My hope above all others

Is that I could be your wife.

I thought, “What is my mother doing with this poem on her bed when she died—a poem about death and divorce? I thought things were over between her and Dad.”

I read onward through rhymed stanzas of loss until I reached the poem’s end,

Love must not linger wishfully

When oblivion is its end;

May I wish you happiness beyond compare,

And just to be your friend.

The poem served as my mother’s “Dear John” letter mailed to my father in the last days of their marriage. It signaled the end of their relationship and offered the hope of friendship. I grew up ignoring my mother’s poetry. Now that she died, I combed her poem for clues to the riddle she gave me in her last telephone conversation: “There is more to the story.”

When my brother, Jaison, and his wife, Franchesca, arrived to help with the funeral arrangements, I read “Oblivion” to them. Although gray with grief, they listened as I laid out my case. “I’ve heard of twins and elderly couples dying close together. First one dies and then another. You think, ‘Oh, how romantic. The couple has to be together even in death.’ Remember our Sunday School teachers, Carl and Charlotte Anderson?”

My brother nodded a bristled face.

I continued, “When Carl died, Charlotte died soon afterwards. You could not stop her. It was as if she could not live without him. It may not have been a coincidence that Mom died eleven weeks after Fred.”

Franchesca objected, “But your parents have not been together for over forty years. They lived in different states.”

“I know, but why did Mom have this poem on her bed when she died?”

The three of us stared at the riddle. The answers to our many questions escaped us. There was some connection between our parents which transcended time and death.

In 1985, my father wrote a letter asking me to retrieve his poetry if anything ever happened to him. When he died and my nephew found my response in a box of scrap paper, I traveled numerous times to Albuquerque to grab every poem I could find in his pottery studio file cabinets. I brought empty suitcases to pack. I bought boxes at Staples to fill and ship. I even rented a pickup to drive his poetry, pottery, and pictures across three states. I stand before my guest bedroom closet packed to the ceiling with plastic file cabinets containing my father’s memories. I stored more items under first one and then two guest beds. When I ran out of space there, I stored plastic storage bins in my bedroom closet, and, when I ran out of space there, I stored boxes and bins in the place of last resort before a paid public storage unit--the garage.

One of my father’s poems I found was titled “The Unshadowed.” It mirrored stanza-by-stanza my mother’s poem “Oblivion.” His poem told his version of the divorce, mocking her opening lines with his,

Perhaps another world,

certainly another place!

If not this time in space,

certainly another place.

Like Jessie, Fred proposed marriage “perhaps in another world.” The date at the bottom of April 1970 corresponded to the dates I found on court documents of their divorce, which finalized on May 7, 1970. I did not find a copy of my mother’s poem at my father’s house and I have yet to find a copy of my father’s poem in my mother’s apartment or storage unit. Their poems are so similar, that I reconstructed that Jessie sent Fred her poem during the final days of the court proceedings. Her “just to be your friend” line was a conciliatory olive branch. Fred had none of it. He threw her poem back in her face, mocking her stanza by stanza. He filled his poem with imagery of table saws, needles, and paper cuts—imagery of blood and castration.

I print here my parents’ divorce poems side-by-side so you can examine how they communicated with one another through poetry. Jessie’s poem “Oblivion” is on the left and Fred’s poem “The Unshadowed” is on the right. You can read straight down on the left or right side to read their poems separately, but when you read zigzag from stanza to stanza, like a ping pong match, you hear their conversation in poetry.

If I could live in another world,

Or have another life,

My hope above all others

Is that I could be your wife.

| Author Notes |

I conceived of "Poetry and Poison" in 2012 when both of my parents, potter Fred Robert Wilson and poet Jessie Lee Dawson-Wilson, died eleven weeks and eight hundred miles apart. They left me hundreds of poems which bore striking resemblance and communication with one another, but I was so grieved with my parents' loss, I did not know how to approach the subject.

Enough time has passed for me to piece together their lives through their poetry. Part poetry and prose, essay and story, romance and mystery, "Poetry and Poisons" shows that the words we leave behind can either haunt us or liberate us. I will initially write about seven chapters to expand later. I will submit individual chapters for publication. I thank Angelheart for use of the image "Speaking Poison." |

![]()

By Sis Cat

Last Paragraph of Chapter 1:

Back in my mother’s apartment, I presented to my brother and sister-in-law a brittle sheet of typed paper I found in our mother’s bedroom. “Mom wrote a story about how she first met Fred.”

Chapter 2

“Get outta here.” My brother Jaison shook his head at the thought of the man who left his children so young, they never became comfortable calling him dad. “You gotta be kidding me.”

“No.” My hand raised the sheet like a lawyer raises evidence in court. “Mom wrote it in the mid-sixties as part of a story after she met Fred.” I pointed to the number three typed in the upper right hand corner. “I only found the third page. I do not know what happened to pages one or two if there is any more. Do you want to hear it?”

“You bet I do.” Franchesca leaned forward and tossed back black hair which had hung over an ear.

Like a town crier, I held the sheet on both edges and read,

Jessie L. Wilson 3

30814 San Martinez Rd.

Saugus, California

I volunteered to finish preparing the refreshments and got busy. With everything completed, I decide to browse through the exhibit—viewing paintings, ceramics, textiles, and sculptures. A strong feeling of purpose crept over me.

One little sculpture seemed to impress me more than anything else in the entire exhibit. I asked the artist about purchasing the little 18 inch woman with a worried look on her face, offering to pay $5.00 down and $5.00 a month until the price of $25.00 was paid.

With a very concerned look on his face, he demanded, “Why do you like it?”

“It speaks to me,” I replied.

“If you really get the message,” he continued, “you can have it,” pushing it toward me.

Again his overt manner disturbed me. I questioned his reasons, wondering why he was giving me the sculpture. At first he was extremely evasive. Then he impulsively dragged his index finger from my forehead down across my lips, smearing my make-up as he went. While looking at his raised finger, he whispered softly, “Behind all your powder and paint, I discern a spiritual soul.” He turned and walked swiftly away, greeting some people who were entering the exhibit—leaving me dumbfounded.

Six months later we said our marriage vows in an artistic “Sundown Wedding.” The little sculpture, “Woman of Pain”, is still in our art collection. It is not for sale; it is a connecting link in our marriage.

I finished reading the story fragment. Our mother dead for less than twenty-four hours, we began an autopsy, not on her body at the Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office, but on her writings scattered and stuffed around a San Fernando Valley three-bedroom apartment. I closed my eyes and recollected. “I remember Mom telling me last month that she met Fred at a fashion art show. He was an artist and she was a model.” I opened my eyes to the actual story our mother wrote around 1963 after she met our father. It was not the whole story, but it was a lot more than the “I met him at a fashion art show” one-liner she told me two weeks before her death.

The three of us dissected the fragment. “He ran his finger down her face and ruined her makeup!” I ran my index finger from my brown forehead, down the ridge of my nose, and past my lips.

Franchesca cringed, as if Fred ran a finger down the middle of her makeup. “Why would he do that?”

My brother shrugged at his Italian American wife. “I don’t know.”

I proposed, “Mom was light-skinned and looked white. Fred ran his finger through her makeup because he wanted to see if she was white or a black woman wearing white makeup.” Raising my index finger and thumb, I rubbed imagined foundation makeup between them and mocked my father’s pickup line, elongating the "o" in "soul." “Behind all your powder and paint, I discern a spiritual soul.”

The three of us laughed, even though we had two memorial services to plan—one for our mother and one for our father. Jaison waved the paper away. “I can’t believe she fell for that line.”

Franchesca relaxed her face from its imagined violation by my father’s finger. “I wonder what happened to the other pages of your mother’s story.”

Huddled in the only clear space in our mother’s cluttered bedroom, we glanced around at shelves and desks buried beneath books and papers. The closet was so full of boxes and clothes, that our mother strewed garments on the back of a chair, too full to sit upon. We hoped that pages one and two, and, perhaps, many more would be sitting atop a pile of papers. We sighed, not wanting to undertake the excavation. In a flash, we all thought the same thing: “The storage unit.”

The storage unit door bulged outwards. Two weeks before our mother’s death, Terry had turned the combination padlock. The lock clicked and clinked. Lock opened, we dodged to the side of the door and swung it. We waited. Instead of an avalanche, the crushed boxes released a sigh as they bulged a further half inch into the doorway. The damp smell of mold and decayed paper wafted from the cavernous space, its busted ceiling light unrepaired. Terry snapped a white ventilation mask over his black face. He looked like a Stormtrooper from Star Wars. The mask jiggled as he spoke. “What are you looking for?”

“I’m looking for my writings and anything from Fred.”

Now, with our mother’s death, I must retrieve her papers, too, and find a place to store and analyze them in my condo running out of space. Sifting through the family storage unit will consume my weekend visits to Los Angeles for years to come. Leaving behind the florescent-lit hall of the public storage, I entered the cave and climbed a mountain of paper.

| Author Notes | I owe a debt of gratitude to my late mother, Jessie Lee Dawson-Wilson, for giving me life and the inspiration for this novel which incorporates her writings and that of my father, potter and poet, Fred Robert Wilson. The story fragment quoted about how they first met is Jessie Wilson's writing from around 1964. I do not know its title, but if you want to find out what else I uncovered about this story, you will have to read the next chapter. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

The damp smell of mold and decayed paper wafted from the cavernous space, its busted ceiling light unrepaired. Terry snapped a white ventilation mask over his black face. He looked like a Stormtrooper from Star Wars. The mask jiggled as he spoke. "What are you looking for?"

"I'm looking for my writings and anything from Fred."

Now, with our mother's death, I must retrieve her papers, too, and find a place to store and analyze them in my condo running out of space. Sifting through the family storage unit will consume my weekend visits to Los Angeles for years to come. Leaving behind the florescent-lit hall of the public storage, I entered the cave and climbed a mountain of paper.

| Author Notes |

LIST OF CHARACTERS:

Andre: The main character and narrator of "Poetry and Poison." He embarks on a quest to uncover the secrets of his deceased parents using the poems they left behind. Jessie: mother of Andre and a poet who died without finishing her story about how she meet his father, Fred. She is Fred's ex-wife. Fred: poet, sculptor, and father of Andre, and ex-husband of Jessie. Fred dies without telling his side of the story about their divorce. Kristen: Third wife of Fred. She acts as guide to helping Andre understand his father. Terry: brother of Andre. Terry acts as guide to helping Andre understand his mother. I would like to thank Angelheart once again for the use of her image. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

Now it was Fred’s turn to be dumbfounded. Unlike his abandonment of Jessie the night before, she did not turn and leave, but waited for his approval. This woman had discerned his soul and gave of herself her only talent—poetry. This soul poet had matched his soul artist. “Why . . . why, thank you. No one had ever written me a poem before.”

"You're welcome." If Jessie’s smile widened further, it would have wrapped around her powdered face.

They started dating and became engaged, but is “Soul Artist” the poem Jessie gave Fred?

| Author Notes |

Yes. At an impasse about this book, I wrote this chapter while seated on the spot where my mother died years ago.

LIST OF CHARACTERS: Andre: The main character and narrator of "Poetry and Poison." He embarks on a quest to uncover the secrets of his deceased parents, using the poems they left behind. Jessie: mother of Andre and a poet who died without finishing telling him her story about how she meet his father, Fred. She is Fred's ex-wife. Fred: sculptor, poet, father of Andre, and ex-husband of Jessie. Fred dies without telling his side of the story about their divorce. Kristen: third wife of Fred. She acts as guide to helping Andre understand his father. Terry: brother of Andre. Terry acts as guide to helping Andre understand his mother. Photo of tar bubble courtesy of Google images. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

Now I understood the poem I had found in my mother’s bedroom the day after she died. She had scrawled it on the first page of a Japanese notebook on January 22, 1967:

I write because I must and I must because I must, must, must.

She had left the rest of the notebook pages blank. I read this poem at her memorial service. Now I write because I must, must, must.

Dawn lightened the cobalt sky I glimpsed through vertical blinds. I closed my laptop and captured some sleep before a non-stop day of church, shopping, lunch, and recitals with my family.

Afterwards, I had to leave what remained of my family and drive up north to San Francisco. With a backpack slung over my shoulder, I stepped backwards out of my mother’s bedroom to take one last look at the boxes that awaited my next visit. I paused in the doorway, kissed the tips of my fingers, and pressed them to her door. “Thanks, Mom, for the inspiration.”

| Author Notes |

smaze=a mixture of smoke and haze.

I reformatted the poems due to limitations of what I can achieve with not-so-advanced Editor. Chapter 3 includes the complete text of Jessie Wilson's poem "Soul Artist" if you wish to compare it to Fred Wilson's poem "What is the Right Chemistry?" One person writes a poem at the beginning of a marriage; the other person writes a poem at the end. These are among several sets of thematically linked poems I uncovered. The picture is from Google Images and is typical of the signs I saw posted in front of dead almond orchards in drought-stricken California. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTERS: Driving through stop-and-go traffic, I saw through the haze in my mind an answer to my father’s question, “What is the right chemistry?”

“If you want to know if a couple has the right chemistry,” I said, “study their poetry.”

Scanning the freeway to see if police watched to ticket me for “distracted driving,” I steered with one hand and grabbed my iPhone with the other to record a thought I may use later: “Just because opposites attract, does not mean they should attach.”

I saved my recording and replayed it through my car speakers: “Just because opposites attract, does not mean they should attach.”

“That sounds about right,” I said, and drove into the haze of distant wildfires.

| Author Notes |

Yes, the Poets of the Square Table existed. Housed in the Hercules Public Library on the last Monday of the month, the poetry club welcomed me as a "visitor," but did not accept me as a full member--a poet or knight. The club held its last meeting on January 28, 2013. I changed the names of the members to suggest the names of King Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere.

The previous chapters focused on the poetry of my parents Fred and Jessie Wilson to uncover who they were. This chapter opens up a second front--the examination of the sculpture of Fred Wilson to uncover why Jessie connected with him. Image of the Knights of the Round Table courtesy of Google. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPH OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

The Poets of the Square Table disbanded their fellowship until the following month. My appearance there on August 27, 2012 marked the first time I shared my parents’ poetry in public after their deaths weeks earlier. I did not know then that when I later became a poet, writer, and storyteller and created a spreadsheet listing hundreds of readings and performances, I would list the Poets of the Square Table as my first public event. The poets planted the idea in me of telling my parents’ story through their poetry, but I had overlooked their second idea: telling my parents’ story through Fred’s sculpture. Jessie wrote that Woman of Pain “is a connecting link in our marriage.” If I can find the sculpture, I could find the “connecting link.”

| Author Notes | My book "Poetry and Poison" will be more like "Pottery and Poison" for several chapters as I explore the sculptures of my father Fred Robert Wilson and their role in his marriage to my mother Jessie Lee Dawson. My conclusions are subject to change based upon what I uncover. The image is of the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial in Washington, D.C. by Roberts Betts. Through articles, I confirmed that my parents met at a fundraiser for this monument. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER:

My thoughts returned to my present research in my father’s scrapbook, which lay open on the bed. I refocused on the “Fashion Show” article and read the next paragraph:

Great sculptors on occasion heighten their message by deforming their figures. Wilson utilizes this approach in his sculptural portrayal of the idea that the world will eventually become a woman’s world.

The world will eventually become a woman’s world? A paper published my father in 1963 as portraying and prophesying this? Now, I was really curious to discover what sculptures my father exhibited at the fashion show and why. As my mother wrote, “One little sculpture seemed to impress me more than anything else in the entire exhibit.” Who was the Woman in Pain?

“Andre, I found something.”

Over the phone, the voice of my brother, Terry, choked with tears. Did he find the Woman in Pain—the wood carving our father gave our mother when they first met? I pressed the receiver to my ear. “Is it Fred’s sculpture?”

Terry sobbed. He dribbled words one at a time. “No . . . it’s . . . Mom’s . . . writings.”

“What’s it about?”

“I can’t tell you over the phone.”

What couldn't he tell me over the phone? Why the tears? I changed strategy to snatch the information from him. “Could you scan and email it?”

“No, I’ll just wait until you get here.”

Terry piqued my interest. I had planned a trip to Los Angeles the next day to attend the memorial jewelry show that my father’s widow, Kristen, staged at the house of his former pottery student. I cracked my knuckles. My hands ached to grip the document Terry found. A clue to our parents’ marriage?

I flew to L.A. and stepped into my mother’s apartment. Strange how I referred to it as “my mother’s apartment” as if she still lived here. My siblings, Terry and Joi, had drawn the blinds. Shadow pervaded the rooms. A mountain of brown flowers, once yellow, including those which had lain on our mother’s casket, decayed on the dining room table. The memorial service had occurred three months earlier.

As I sat on my mother’s bedroom floor, I sorted her boxes of papers on the spot where she had died—a green patch of carpet beaten down from foot traffic and from praying on her knees. I heard breathing and footsteps behind me. I turned. My brother Terry teetered in the doorway, papers in hand, tears in his eyes. “This is what I found.”

His hands trembled. I grabbed the sheets. The typed pages appeared brittle. The room darkened as I read:

| Author Notes |

"After the Sun Went Down" is an actual essay that my mother, Jessie Wilson, wrote about her bout with mental illness. I cut the story by a third to fit as a story within a story. Her essay is undated, but newspaper accounts of her marriage to Fred Wilson state that she was a free lance writer. I estimate that she wrote this between 1959 and 1963. I would deeply appreciate insight from people who have dealt with the issues she addressed in her essay.

The images are of my father's sculpture Pregnant Lady as it appeared in 1960 and today. I thank Dean Kuch for instructions on how to use Photobucket. Thank you for your review. |

![]()

By Sis Cat

LAST PARAGRAPHS OF PREVIOUS CHAPTER

“Do you recall a period in your childhood when Mom didn’t live with you.”

I heard silence on the other end of the phone. Terry broke it. “Come to think of it . . . there was a period when Mom did not live with us?” He referred to himself and our oldest brother Dion.

“How long was it?”

“Oh, a couple of weeks . . . maybe a month.”

Mom was in a mental hospital for a month. Her essay made it sound like she stayed a couple of days. “What happened to you guys? Who took care of you?”

“We went to live with Aunt Edna up in Oakland, and then she came down to live with us in Los Angeles. Grandma Dawson came to live with us, too, and cousin Thaddeus. We were living on 57th Street then.”

I opened the kitchen drawer, grabbed a marker, and wrote notes on the refrigerator dry erase board. “When was this?”

“About 1961.”

1961? That was two years after the events chronicled in our mother’s essay but two years before her marriage to Fred. Are we talking about the same commitment to the psychiatric ward, or did she have a relapse after her essay concluded with “a different Mommy would be coming home to four little waiting arms”?

“Did anyone explain anything to you what was happening to Mom?”

“No one explained anything to me. You may want to talk to Dion. He’s older than me and may provide more information or a different perspective.”

I added “call Dion” to my mental to do list and asked a final question. “Did you notice any difference when Mom came back from the hospital?”

“I really could not tell any difference. She was her regular Mom self.”

In August of ‘63, Dr. Martin Luther King thundered his “I Have a Dream” speech before a crowd of 200,000 in Washington, D.C. Five months earlier, Fred Robert Wilson had a dream, too—to design the Capitol’s first monument to a Negro, educator and civil rights leader, Mary McLeod Bethune.

Around the country, local chapters of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) held fundraisers to erect a monument to its founder in Lincoln Park and not on the National Mall. When the Fine Arts Committee of the Los Angeles chapter of NCNW announced plans for a fashion show and art fundraiser a week before Easter 1963, Fred pounced on the opportunity to win the commission and “breakout” from being a potter. He accepted a slot on the program alongside Rosalind Whelden, a UCLA art instructor who lectured about the role of art in contemporary America; Yong Ho Chi, a Vietnamese painter who demonstrated portrait techniques; and a Negro soloist named Julius Caesar, of all things. Fred planned to stand out from the “rabble.”

In the months leading up to the event, Fred carved and sculpted women—Indian Woman, Woman in Pain, Hold on Little Woman, Calling Mother. Measuring less than three feet high, these sculptures showcased his potential as a monument maker if they were enlarged to life size. They also appealed to the women who would decide the Mary McLeod Bethune Monument.

Since 1962, as the Civil Rights Movement swirled around him, Fred sensed that the roles of men and women would change in the 1960s. Women's emancipation would become the next great social movement to sweep the country and the world. He planned to become its sculptor.

He sculpted “Ductless Man.” It portrayed a nude woman holding what appeared to be a gangly boy clinging to his mother but was a man who had shrunk while the woman grew. If people confused the two as mother and child, he explained, “This sculpture is about the dwindling stature of man. As woman reaches her full potential, man becomes a child in the arms of woman.”

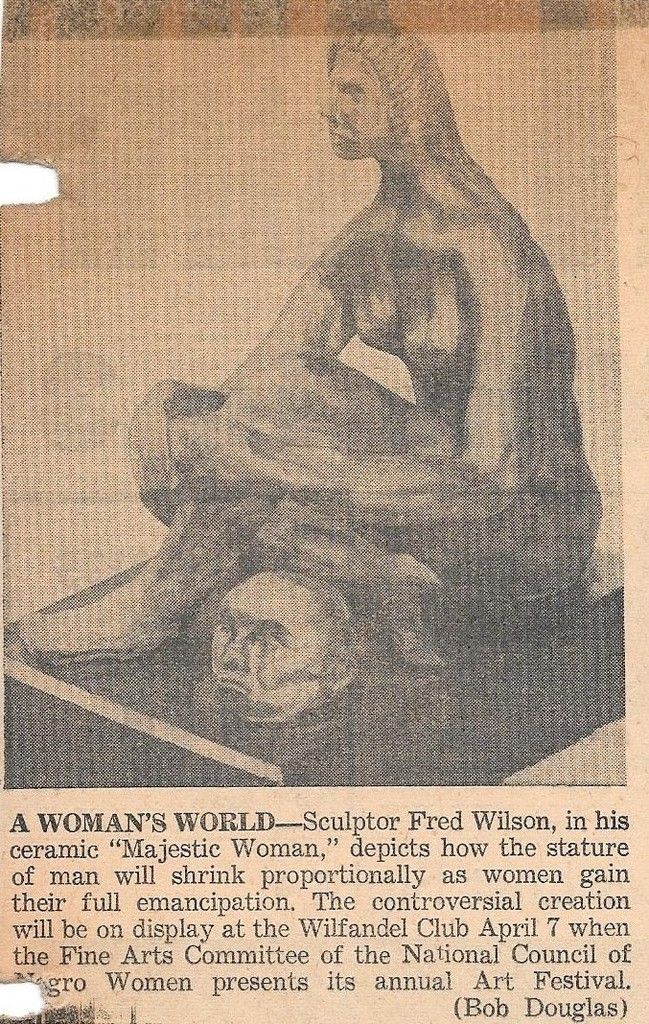

He solved this perception problem with “Majestic Woman.” Instead of a standing nude woman, he portrayed a seated nude woman behind the head of a man. While she grew to majestic stature, his body shrank so that all that remained was his full-sized head, alive and staring in wonderment at the changed roles of men and women. Borrowing an idea from his idol Michelangelo, who had portrayed himself in sculptures and murals, Fred portrayed himself in the head of the bald man.

He would prove that he could compete in the art world as he did in the sports world as an athlete in football, basketball, and track in high school and college. He also played chess. Life was a game of chess. With only two weeks to go before the art festival, Fred picked up the phone and called The California Eagle, a Negro newspaper in Los Angeles.

On the morning of Thursday, March 28, Fred’s clay splattered hands opened the paper. He grinned at a photo of Majestic Woman atop page two. He read the caption:

A WOMAN’S WORLD—Sculptor Fred Wilson, in his ceramic “Majestic Woman,” depicts how the stature of man will shrink proportionately as women gain their full emancipation. The controversial creation will be on display at the Wilfandel Club April 7 when the Fine Arts Committee of the National Council of Negro Women presents its annual Arts Festival.

He rolled the word “controversial” around in his mind. Controversy improved sales, and may win him the Bethune commission. He skimmed over the other artists and the fashion show plans mentioned in the article and read the parts about himself:

Great sculptors on accassion heighten their message by deforming their figures. Wilson utilizes this approach in his sculptural portrayal of the idea that the world will become a woman’s world.

The former athlete, never a great speller, Fred had misspelled in his written statement he gave the paper the word “occasion” as “accassion.” The editor, figuring it was an artsy French word, left it uncorrected. The beginning of the article, “Art Festival to Show Sculpture, Painting,” also titled the sculpture as Magnificent Woman instead of Majestic Woman. Despite the flaws, publicity was publicity. C. Marie Hughes wrote seventy-five percent of the article about him. She concluded by mentioning his art awards at county fairs and his study at California state colleges. With half-moons of clay embedded under his fingernails, Fred cut out the article and prepared for the show.

#

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa, men have named you

You're so like the lady with the mystic smile . . .

Nails scrubbed, Fred, dressed in a black suit and a skinny tie, groaned as the daughter of the NCNW Fine Arts Committee chairman, A. C. Bilbrew, crooned Nat King Cole’s song “Mona Lisa.” Behind the singer dressed like Lena Horn, a woman artist drew back a red curtain to unveil her huge reproduction of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Three months earlier, the Louvre Museum had loaned the world's most famous painting to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, where a million people thronged to glimpse the painting for twenty seconds each. The NCNW hoped to replicate that Mona Lisa magic with a replica on the West Coast. Filling the Spanish-style Wilfandel Club, a crowd of Negro society women, dressed in Easter finery, hats, and gloves, oohed at the reproduction painted by one of their own. Like exotic birds, they fluttered before the canvas.

Noticing that his own sculpture was not getting attention during this spectacle, Fred wriggled his nose at the artist. She’s nothing but a paint-by-numbers hack. And why are these Negro women praising a bad copy of a white artist?

The piano tinkled. The guitar strummed. The chairman’s daughter sang:

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there and they die there

Fred shoved his hands into his trouser pockets. His polished shoe kicked the carpet. Connections. Connections. It’s all about connections. She only got this singing gig because she’s the chairman’s daughter. How about connections helping me get the Bethune commission?

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa.

The solo ended, thank God. The crowd applauded as the daughter curtsied before the Mona Lisa reproduction. This was real art, the NCNW members acclaimed, and we will auction it off to erect a monument to our beloved founder, Mary McLeod Bethune. Fred sighed.

The rest of the art festival progressed. The NCNW auctioned off “Majestic Woman” to raise money for its cause. The paper’s publicity helped. Some of his smaller sculptures, paintings, and textiles sold, too, with a portion of the proceeds going to the organization. He rocked on his heels. Play nice, Freddie. Play nice.

He made it a point to compliment A. C. Bilbrew. She chaired the Fine Arts Committee which would decide the monument. The tall woman wore a corsage that matched her hat. He shook her gloved hands. “Madame Bilbrew, your daughter is a most talented singer.” He placed his hand on his chest. “I am honored that you invited me to participate in your art festival.”

The woman smiled and nodded. Her hat bobbed. “Why, thank you, Fred. It’s all for a good cause.”

Still no word yet on whether or not he would receive the commission.

He distracted himself by watching the spring fashion show. The models formed an Easter parade down a red carpet. Floral arrangements of lilies, orchids, and daffodils lined the runway and were pinned to the bodices of both the models and women in the audience. The air filled with their fragrance. The gowns swished and their beads rattled. The models appeared to float down the runway rather than walk.

The emcee narrated, “Velma Steverson wears this cotton candy confection of melon chiffon. It comes with a jeweled jacket and a matching jeweled bodice in a floral design. This gown is available at Ruby’s French Shop.”

The audience oohed and leaned forward to examine the fabric. Fred grimaced. Women dress for women. They have to go out and spend money to impress other women. Women have been told, “Forget about love. Money is the most important thing.” I’m trying to tell them to save their souls. Love is still the basic thing.

Love.

Fred had just passed his thirty-first birthday a virgin. Perhaps if his Aunt Liza hadn’t burned his hands on the kitchen stove when she caught the boy masturbating, things would be different. Perhaps if his mother Mama Jennie had stayed in Chicago where there were plenty of Negros instead of following a soldier to Victorville, California where there were few, things would be different. White college administrators only admitted him to desegregate their campuses along with a Negro girl if he promised not to date the white ones. Perhaps if the handpicked Negro female students had expressed interest in him, things would be different. Perhaps.

Fred dreamed of marriage. He had carved two statues titled Wedded Bliss, showing an entwined couple. If only his sculptures of women came to life, like Galatea did for Pygmalion, he would find a wife.

Observing the models at the fashion show, Fred saw them as untouchable. They towered in their high heels and hairdos. He felt small, like that tiny, ductless man clinging to the giantess in his sculpture, or, smaller still, the man’s head sitting at the foot of an Amazon. Who could love a man with clay-covered hands and a clay-splattered bald head?

One model caught his eye because she stood out from other Negro models. She appeared white. Was she a Negro, white, or a Negro woman wearing white makeup? He could not decide. He found himself thinking of the line in that song the chairman’s daughter sang:

Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa?

Or just a cold and lonely lovely work of art?

Wrapped in a Botticelli cloud of chiffon, the model drifted down the red carpet and paused at the end. Her smile never changed. The emcee narrated, “Jessie Thompson wears a yellow chiffon gown with a bodice of dropped pearl loops and crystals. This gown is available at Ruby’s French Shop.”

As the model turned to walk up the runway, the hem of her gown swirled to rise and fall. She disappeared into the model area. Fred raised his eyebrows. She will always be a mystery to me.

The fashion show ended. Fred worked the crowd to make sales and connections. Hope this charm offensive works to get me the commission. A group of women in black cocktail dresses accented with orchid corsages confronted him. A woman who wore a turban of ribbons and flowers looked to her friends for approval before making her comment to him. “Fred, I noticed a pattern in your sculpture. You have these oversized women with undersized men.”

Fred regurgitated his well-oiled artist statement. “I believe this world would eventually become a woman’s world. The stature of man will shrink proportionately as women gain their full emancipation. Once man recognizes women’s great potential and their proper place in society, man will rise once again to the stature he at one time maintained.”

The women smiled and nodded at him and each other.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed that the “white” model gazed at his Woman in Pain. She wore a black cocktail dress with pearls now, but her hair still rose in curls. He turned to the women around him, said with a slight bow, “Excuse me, ladies,” and left them. He whisked across the exhibit room, dodging guests and pedestaled sculptures, but he slowed as he approached the woman. No amount of makeup could hide the hint of sadness he saw in her face which echoed the worried look on his sculpture. She snapped out of her daydream and noticed him. “Oh, you’re the artist?”

He heard the just-off-the-plantation Southern accent in her voice. He lost his Chicago accent in California, but not his speed. “Yes, Fred Wilson.”

“Jessie Thompson. Pleasure to meet you.” She extended a white gloved hand.

He hesitated grasping it, fearing he may still have clay remnants somewhere on his hand. He allowed her to grip his hand, firm yet delicate.

She glanced at his bald head. He noticed her eyes looked up for a split moment. Embarrassed that he saw her looking at his scalp, she stared at the carving. “How much is this?”

Fred rubbed his hands. “That will be twenty-five dollars.”

She reached for her beaded purse. “I’ll pay five dollars down and five dollars a month until the price is paid.”

Fred marveled that the model could talk and make unprogrammed moves. All the robots do is walk down red carpets and smile. Now, one stood a living, breathing woman in front of him, a Galatea come to life. Only a sculpture separated him from Jessie. He knitted his brow and pointed. “Why do you like it?”

“It speaks to me.”

Everyone had praised his sculptures of oversized women with undersized men, but Jessie was the first to notice this small carving of a lone woman in pain. Perhaps if he gave her the statue, he could lessen her pain. He pushed the sculpture towards her. “If you really get the message, you can have it.”

Panic and confusion crossed her face. He could tell she thought he wanted to give her the sculpture in exchange for a date. Men hit on models all the time.

“Why are you giving this to me?”

He averted her glare. His shoulders shrugged to buy time. Think fast, Freddie. Think fast. He pressed his index finger on her forehead and dragged a line of smeared makeup along the bridge of her nose and across her red lips. He examined the makeup on his raised finger and whispered, “Behind all your powder and paint, I discern a spiritual soul.”

She stood there, dumbfounded, with a line down her face, as if she had a split personality.

Better beat a fast retreat, Freddie, before she throws Woman in Pain at you. That would be some real pain—getting hit up side your bald head by your own sculpture.

He turned and sprinted to the door. He greeted the guests entering the exhibit and buried himself in the crowd of women—his Amazon bodyguards—to dissuade Jessie from following. He tensed, waiting for a tap on his shoulder and a slap across his face.

Don’t look back, Freddie. Don’t look back.

TO BE CONTINUED

| Author Notes |

The chief thing I accomplished in this chapter was to get out of the way and let my parents tell their own stories. For my father, I stitched together dialogue by using direct quotes from interviews. Yes, those were his thoughts at the time. I also took my mother's written account of her meeting my father (Chapter 2) and rewrote it to tell his story from his perspective. I had fun with this chapter. When you know your characters well enough, they could write their own story.

Yes, the Los Angeles chapter of the National Council of Negro Women unveiled a reproduction of the Mona Lisa while the chairwoman's daughter sang the Nat King Cole song. |

|

You've read it - now go back to FanStory.com to comment on each chapter and show your thanks to the author! |

![]()

| © Copyright 2015 Sis Cat All rights reserved. Sis Cat has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work. |

© 2015 FanStory.com, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Terms under which this service is provided to you. Privacy Statement